Fostering

To maximise efficiency during lambing, triplet and orphan lambs are often fostered onto ewes with a single to reduce the number artificially reared. This is not always simple and the long-term acceptance rate by the ewe may be less than 60 per cent.

There is limited research to show the success rates of the various methods of fostering, however overall growth rates and carcase conformation in small-scale studies were improved in fostered lambs compared to those artificially reared.

Figure 1: Rejected foster lamb. Note the size disparity between the lambs

Select appropriate foster ewes: in good physical condition, free from signs of disease, and crucially with two functional teats. If there is any suggestion the milk supply may be compromised, the ewe is not a good candidate to foster a lamb.

If a ewe has lost her lamb due to abortion or stillbirth, or there is any indication infectious disease may have contributed to her lamb’s death, the ewe is not suitable for fostering. She may pass infection on to her new lamb, which if retained for breeding, could spread disease and cause more abortions. This is particularly true of Enzootic abortion (EAE), but unless a definitive diagnosis is made prior to any fostering decisions, it is better to avoid the situation.

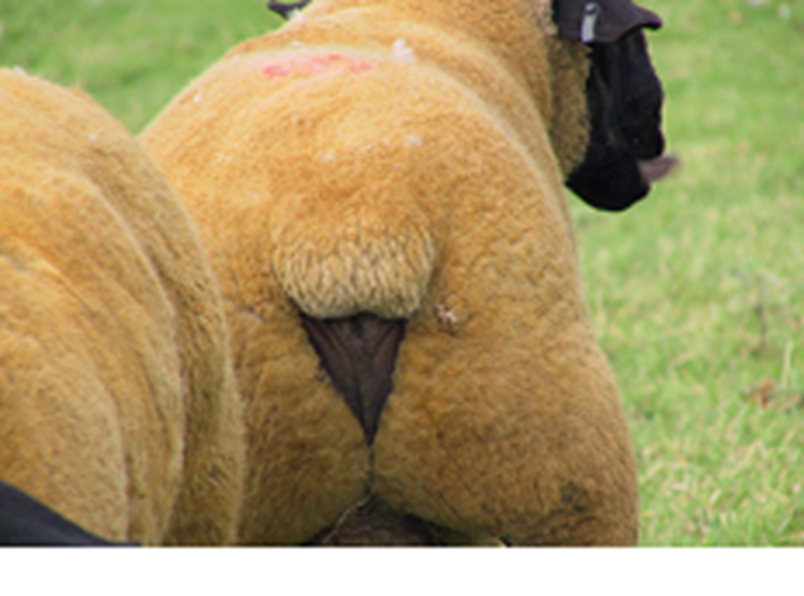

Figure 2: Successful fostering

Orphan lambs

Orphan lambs are triplet or twin lambs removed because of poor dam milk yield, or whose mother has died or is unwell. Many of these lambs have not had enough colostrum immediately after birth and are prone to a wide range of bacterial diseases during the neonatal period including joint ill, watery mouth and respiratory disease. Older lambs may have been hungry for several days before removal from the dam, reducing growth rates and resilience to disease.

It is recommended that "surplus" lambs are removed from the ewe as early as possible as they learn to suck more quickly from an artificial teat than if left with their dam for two or three days. The smallest triplet of every litter should be removed within hours of birth, topped up with colostrum, and either fostered immediately or reared artificially. The ewe and two remaining lambs could then be turned out to pasture the following day.

Transfer of foetal fluids

Rubbing an orphan lamb in the foetal fluids of the newborn single lamb before the ewe licks her own lamb is the most successful fostering method. The best acceptance rates are achieved when the foster lamb is as young as possible, preferably newborn. Due to size difference between the new "pair" of lambs (e.g. a 6-7 kg singleton and a 3.5 kg triplet), ensure the larger lamb does not bully its new sibling. This method of fostering will only work in the period immediately after lambing - once the foster ewe has licked her own lamb dry she is unlikely to accept another lamb, and foetal fluids reduce as time passes, so acquiring enough to cover a days-old orphan lamb may prove a fruitless exercise.

Skinning lambs

Fostering lambs onto ewes who have lost their lambs with the aid of the dead lamb's skin generally has good success. This method may be used in older lambs, although confinement in a small pen for a few days may be necessary to ensure the ewe has fully accepted her new lamb before being turned out.

Figure 3: Confinement of ewes with foster lambs may be necessary for a few days.

Foster crates

There are many designs of foster crates, which hold the ewe in place so the foster lamb can feed and prevent her injuring the lamb. This ensures the lamb receives adequate nutrition if the ewe is reluctant to accept it, and over time some ewes will come to accept the foster lamb as their own. It is essential that clean water and good quality forage or mixed ration is always available and within reach of the ewe. Concentrates should be fed at least twice daily. Inadequate ewe nutrition leads to poor milk production and poor long-term acceptance rates.

Figure 4: Ensure clean water and feed are always available to maintain the ewe’s milk yield.

Rope halters

The use of rope halter provides limited freedom and improved comfort for the ewe compared to the foster crates, provided the halter does not tighten across the bridge of the ewe's nose, and she is able to lie down. Halters should be made of soft rope and not a single strand of baler twine. Attaching the rope around the ewe's horns is an unacceptable practice.

Figure 5: Soft nylon halters must be used; single-strand baler twine is not an acceptable substitute.

Rejection of foster lambs

The ewe and lambs must be carefully supervised to detect early rejection such as not letting the foster lamb suck, pushing the lamb away, and head butting. Head butting lambs can often be detected by the presence of marker fluid, used to identify lambs, on the ewe's forehead. If these behaviours are persistent despite the use of a skin, fostering crate or halter, then it is probably best to separate the ewe and lamb, and move the lamb onto an artificial rearing system.

Rearing orphan lambs

Orphans lambs that cannot be fostered can be reared successfully on artificial rearing systems achieving good growth rates and a low incidence of digestive disturbances such as abomasal bloat and/or volvulus. This outcome is contingent on ensuring that feeding equipment is cleaned and maintained regularly, and that lambs are fed suitable volumes at suitable intervals throughout the day. Automatic lamb feeders can also reduce the amount of labour required if there are large numbers of orphan lambs to feed.

Figure 6: Artificial rearing of lambs can produce excellent results; the automatic feeding systems are not cheap however

Haphazard feeding of lambs from a bucket and teat system does not work and at weaning such lambs are small, poorly fleshed, pot-bellied and lag behind their peers for many months.

Figure 7: Good management of orphan lambs. Well-bedded, low stocking rate and good ventilation.

The Codes of recommendations for the welfare of livestock – sheep

The section of the codes relating to the care of artificially-reared lambs states:

- Artificial rearing of lambs requires close attention and high standards of supervision and stockmanship if it is to be successful. It is essential that all lambs should start with an adequate supply of colostrum.

- All lambs should receive an adequate amount of suitable liquid feed, such as ewe milk replacer, at regular intervals each day for at least the first four weeks of their life.

- From the second week of life, lambs should also have access to palatable and nutritious solid food (which may include grass) and always have access to fresh, clean water.

- Where automatic feeding equipment is provided, lambs should be trained in its use to ensure that they regularly consume an adequate amount of food and the equipment should be checked daily to see that it is working properly.

- Troughs should be kept clean and any stale feed removed. Automatic feeding systems must be well-maintained and checked daily.

- Equipment and utensils used for liquid feeding should be thoroughly cleansed and sterilised at frequent intervals.

- A dry bed and adequate draught-free ventilation should be provided.

- Where necessary, arrangements should be made to supply safe supplementary heating for very young lambs.

Docking and Castration

Tail docking and castration cause both acute and chronic pain in lambs and there are doubts about whether either procedure is necessary. Fattening lambs sold prior to sexual maturity do not pose a risk to any female sheep on the farm and do not need to be castrated. Castration and tail docking by means of a rubber ring or other device to restrict blood flow to the scrotum or tail must be carried out within the first week of life; it is an offence to castrate a lamb over the age of three months without the use of local anaesthesia. Tail docking, if required, must be carried out to ensure that sufficient tail length remains to cover the vulva in ewes, and the anus in rams.

Recent developments in pain management at castration involves a device (“Numnuts”) which delivers a local anaesthetic at the same time as the elastrator ring is applied. The device is currently being trialled in Australia but is likely to be available in the UK from 2020. Farmer acceptance is the major factor in adoption of new instruments and techniques, but the process could be driven by farm assurance schemes or legislation. Previous devices, such as the modified Burdizzo clamp, proved unpopular due to increased handling time and failure to effectively castrate some lambs.

Figure 8: Tail docking and castration cause both acute and chronic pain in lambs.

There is a lot of very useful advice available contained within the Codes of recommendations for the welfare of livestock - sheep

Figure 9: This 40+ kg 3.5 month-old ram lamb has not been castrated, although the tail has been docked. Ideally neither procedure would be carried out.

Figure 10: It may not be necessary to dock tails of early-born lambs if they will be slaughtered before the blowfly risk period.

Figure 11: Tail docking does not prevent faecal contamination as a result of poor parasite control.

Figure 12: Texel ewe just before lambing - this tail has been docked too short.

Figure 13: Another example of excessive docking

One of the main reasons for tailing lambs is to reduce the risk of blowfly strike. Control of this parasite is covered in detail in another bulletin, but fly strike can be prevented by controlling faecal contamination of the back end by correct parasite control, dagging, and use of insect growth regulators such as dicyclanil. If these methods are carried out effectively then tailing lambs may not be necessary.

Figure 14: Tail docking did not prevent flystrike in this lamb (standing). Shearing the ewes will also help to control blowfly strike in this flock

The industry is actively promoting schemes to reduce tail docking and castration of lambs. In these schemes farmers are encouraged to limit the use of these procedures to specific instances where their vet considers that not undertaking them would compromise animal welfare.