Introduction

Deaths of newborn lambs in the first 48 hours after birth account for almost half of all lamb losses from scanning to weaning (figure 1). This causes significant losses to the sheep sector and impacts on productivity, welfare and farmer morale.

There is significant variation in levels of losses between farms. The Hybu Cig Cymru project in 2011 showed a 15% lamb mortality in Welsh flocks. A UK wide study found a range of 4% to 21% in lowland flocks. The industry target for losses of lambs born alive in the neonatal period is under 6% and some farms are proving is achievable.

Lambs which are born without difficulty, at the correct birthweight, to fit ewes with good mothering ability, will be licked, standing and suckling colostrum within 15 minutes of birth. Their chances of survival with adequate shelter and hygienic conditions are extremely high.

Figure 1. Lambing losses from HCC Lambing Project 2010/2011

The major risk factors for newborn lamb losses are:

- Low birthweight

- Low colostrum intake

- Difficult birth

- Large litter size

- Poor hygiene

- Inappropriate genetics

- Lack of shelter

Many of these risks have common underlying causes with ewe nutrition being one of the most important.

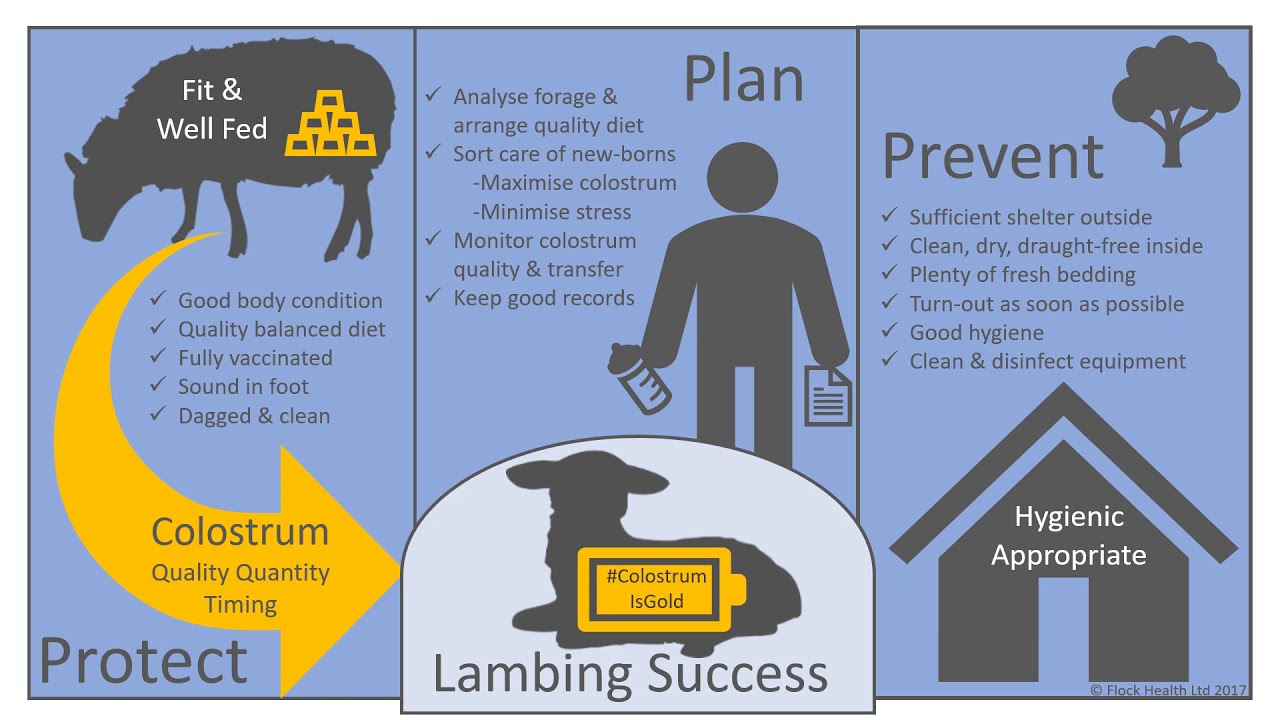

Figure 2. Correct ewe nutrition throughout the production cycle is essential to reduce lamb losses.

Low Birthweight

Small lambs are more likely to die from hypothermia, starvation, infection, injury and predation. They have less reserves of brown fat to generate heat immediately after birth, lower glucose levels for energy and larger surface areas to lose heat. This lack of energy and rapid chilling delays or prevents them getting up to suckle colostrum quickly enough. They are much more prone to infection and more likely to be squashed by the ewe.

The target birth weight for lambs from an 80kg ewe to a terminal sire are:

- Single 4.5 - 6.0kg

- Twin 3.5 - 4.5kg

- Triplet - greater than 3.5kg

Measure and record birth weights to identify if this is contributing to losses and then investigate the cause.

Low birth weights are caused by poor body condition of the ewes in late pregnancy, or through poor nutrition in the last three weeks before lambing for ewes in any condition. Lambs from triples or higher will be smaller and require additional attention and colostrum supplementation. Ewes which are unwell are also more likely to have small lambs.

Figure 3. Sub-acute fluke in ewes can contribute to poor condition and low birthweights.

Low birth weights can be prevented through good ewe management. Condition score regularly to make sure ewes enter late pregnancy fit but not fat. Trying to add condition at this stage is too late. When poor condition is detected investigate the causes - diet, parasites, age, teeth or diseases for example.

Ensure ewes receive the correct nutrition based on scanning results, body condition, forage quality and bodyweight. The ration should supply adequate energy, protein and minerals and be balanced for good rumen health. Ensuring sufficient feed space for every ewe to have access and keeping the ration fresh and palatable are essential to maintain good feed intakes. Adequate access to fresh, clean water should not be overlooked.

Metabolic profiling ewes in the last two to four weeks before lambing is a useful way to objectively measure if the ration is meeting their needs. Small changes in the diet can prevent serious ewe health issues and ensure optimum birthweights.

Ewe nutrition in the last few weeks of pregnancy also has a major influence on udder development. Poorly fed ewes have lower colostrum quality, lower colostrum yield and poorer milk yields through lactation.

Colostrum

Low colostrum intake is caused by poor supply from the ewe, low birth weights, hypothermia, mismothering and multiple births.

The supply from the ewe is lower or poorer in quality if she was too thin or had a diet lacking in energy or protein in the last three weeks of pregnancy, if she had a difficult birth or if she had any other illness.

Small, cold lambs do not stand quickly enough and seek the teat. Multiple lambs, in addition to lower birth weight, have dams with a higher total colostrum volume but less available per lamb.

Mismothering delays suckling and can occur if the stocking density is too high or if the ewe is disturbed during labour for example by people, dogs, machinery or moving fields. First time mothers are more prone to mismothering and require greater surveillance. Hungry or thirsty ewes are also more likely to leave their lambs to seek food and drink.

All lambs must receive sufficient quantity of high quality colostrum quickly. They require 50mls per kg of bodyweight in the first two hours after birth and a total of 200mls per kg over the first 24 hours. All lambs should be checked for suckling in the first two hours.

Figure 4. Colostrum in the lamb's stomach can be detected by gently feeling behind the ribs.

If there is any doubt about suckling the ewe’s colostrum supply should be checked and the lamb helped to suckle. Sit the ewe on her hindquarters and lay the lamb on its side, putting the teat into the lamb's mouth at the same time as gently expressing some colostrum onto the lamb's tongue to encourage sucking.

Supplementary colostrum should be provided to any lambs:

- who fail to suckle enough from their dams despite help because they are small, cold or weak

- whose dam has insufficient supply, poor teat conformation, mastitis or other illness

- that had a difficult birth

- from multiples

The preferred source of colostrum is from the dam if enough quantity can be milked into a clean container. After that, fresh colostrum from a healthy ewe that lambed in the last 12 hours can be collected and used immediately, or refrigerated and used within 24 hours. Ewes colostrum can be frozen for later use but must be thawed in hand hot water to prevent damage to the proteins which provide immunity. Cows colostrum can be used as an alternative but must come from sources with a low risk of Johne’s disease. Artificial colostrum products are useful when no other sources are available but ideally should be used to top up the natural colostrum supplies rather than being used exclusively.

The supplementary colostrum can be supplied by a bottle and teat or by using a stomach tube. All equipment used for providing colostrum must be cleaned and disinfected after every use.

Figure 5. Providing supplementary colostrum via a stomach tube.

Lambs which are too weak to lift their heads up or are unconscious must not be stomach tubed. If they are less than six hours old they will still have sufficient body reserves of energy and can be gently warmed to improve consciousness over one to two hours before feeding. Heat boxes set to 45 degrees, heat lamps or hot water bottles can be used to aid recovery.

Lambs which are found unconscious and over six hours old will not have sufficient energy reserves left and require supplementary glucose in addition to warming before it is safe to stomach tube them. This is provided by injecting 25mls of warm 20% sterile glucose solution directly into the abdomen using a sterile 19G 25mm needle and syringe. The lamb is suspended vertically by the front legs. The needle is introduced through the body wall 2 to 3 cm to the side of and 2 to 3 cm below the navel. The needle point is directed towards the lamb's tail head. The solution is slowly injected into the body cavity once the needle has been introduced up to the hub. The recovery after warming should take 30 to 60 minutes when colostrum must be supplied.

Figure 6. Identify cold lambs quickly. Warm lambs to ensure they can lift their heads before feeding with colostrum.

After the first feed it is essential to check that lambs are continuing to suckle, ensuring the full 200mls of colostrum is received in the first 24 hours and supplementing where necessary. After 24 hours, hungry lambs can be identified by a hollow appearance, increased crying, separation from the dam and standing in a fixed hunched position. The underlying cause must be identified and supplementary care and feeding provided.

Figure 7. Hungry lambs can be identified by their hunched appearance with all four legs in a fixed position

Difficult births

Difficult births cause lamb losses through stillbirths, injuries, delayed suckling and infection or injury to the ewe. They are a much higher risk if the lambs are more than 1kg over the optimum weights. This occurs in over conditioned ewes and also in poor ewes who over eat to compensate in late pregnancy. Single lambs are at a much greater risk of high birth weights if the ewes are not scanned and fed appropriately.

Even at normal birth weights slow or delayed deliveries can lead to difficult births. Multiple bearing or sick ewes are at risk of delayed delivery particularly if they are weak or have pregnancy toxaemia. Multiple lambs can also just get jumbled up in the birth canal.

Any disruption from people, dogs, movements and management tasks can disturb the ewes and delay labour and should be kept to a minimum.

Lambs which get stuck or delayed in the birth canal run out of oxygen and either die of hypoxia before birth or shortly after. All lambs which had a stressful birth are at greater risk of delayed suckling and should be helped to suckle or supplemented with colostrum. Staining of the tail area with meconium is an indication the lamb was stressed in the birth canal.

Lambs delayed head first can have swollen heads and airways and may be unable to suckle and need to be stomach tubed. Severe injuries to lambs can occur during intervention for example rib fractures to large backwards singles or leg injuries caused by excess traction. Assistance with lambing should be carried out by trained personnel using clean, gloved hands and plenty of lubricant. Veterinary help must be sought if the problem cannot be corrected easily and without excessive force.

Figure 8. Rib fractures caused by difficult birth

Ewes which had a difficult birth can have tears to the uterus, cervix or vaginal walls. Full thickness tears into the abdomen lead to death from bleeding or infection. Less severe injuries can cause infection to the uterus,vagina or urinary tract or contribute to prolapses. The ewe will have lower milk yields and be unable to rear her lambs effectively. They should be examined and treated according to the flock health plan protocols, with veterinary assistance sought for severe injuries or suspected tears.

The impact of difficult births vary dramatically between farms. Prompt intervention by competent shepherds can prevent lamb deaths and ensure the ewes and lambs receive additional care. It is much easier to intervene quickly in indoor lambing systems.

Litter size

Large litter sizes are influenced by genetics and by body condition at tupping. Ensure ewes enter the breeding season in the correct, but not excessive condition. Particular care should be taken to maintain and not increase condition in the fecund breeds like Aberdale and Lleyn to prevent high multiples.

Ewes carrying three or more lambs should be identified and separated for separate nutrition and greater monitoring. All lambs should receive additional colostrum and protection from adverse weather and temperature. It may be worth looking at the economics of removing the 3rd lamb to rear separately from the dam.

Figure 9. 20% of lowland ewes have triplets - ewes need to be fed correctly and lambs supplemented with colostrum

Hygiene

Bacteria which build up in the environment contribute to neonatal lamb losses by causing diseases like watery mouth, navel ill, septicaemia, joint ill and mastitis. Specific control of these diseases is discussed in more detail in a separate bulletin.

Bacteria build up during the lambing period and survive and spread in moist conditions. There are a number of ways to try and lower the disease challenge to newborn lambs.

- Outdoor lambing can reduce contamination if there is adequate shelter and appropriate ewe genetics for the conditions.

- Low stocking density in buildings reduces disease risk. Allow 2 sq metres per ewe with twins.

- Buildings with good ventilation and drainage have lower humidity.

- Bedding should be clean, dry and plentiful.

- Sheds and individual pens should be properly cleaned and then disinfected regularly. All equipment including feed and water buckets should be hygienic.

- Isolating sick animals, disposing of afterbirths and having clean hands and overalls will reduce the spread of infection.

Dipping lamb’s navels immediately after birth with strong (10%) iodine solution also helps to prevent bacteria in the environment from infecting the lambs through the navel. It should be repeated after two to four hours and then daily until the navel is dry.

Genetics

Genetics can have a significant impact on lamb mortality. There is a genetic influence to lambing ease, mothering ability, birthweights, lamb vitality, milk yield and litter size. Both indoor and outdoor flocks should be selecting for a reduced need for intervention at lambing.

Breed selection for the conditions is a good basis to ensure the animal will perform well in a system. Some of these traits can also be selected through the breeding rams and ewes by assessing the EBVs prior to purchase. However, lambing ease, mothering ability, milk yields and mortality can all be assessed in the home flock too by keeping good records of individual performance and using them to make culling decisions.

Increasingly, genomics are likely to be used to provide accurate data about the performance of breeding animals and their progeny. This is particularly useful for the traits which are currently less accurately assessed through traditional breeding value measures.

Figure 10. Good maternal behaviour is important to ensure a good start to the lamb's life.

Shelter

Hypothermia remains a major cause of mortality. For both indoor and outdoor systems adequate shelter from extremes of weather and temperatures are required. In outdoor systems ewes should have plenty of opportunity to find sheltered and secluded birthing areas away from disturbance and other ewes, and protected from the weather. Lambing should be timed to avoid the worst conditions and contingency must be available in extreme conditions to provide alternative shelter.