Mastitis in dairy cattle is almost always caused by bacterial infection. Understanding which bacteria are causing mastitis on your farm can provide you with significant information as to what the likely key risk factors are and also, what control measures you need to consider.

Mastitis-causing bacteria can be divided into two groups: environmental and contagious. Environmental bacteria usually come from the environment so spread outside of the milking parlour, while contagious bacteria are generally spread during milking. This division is not complete, some environmental bacteria can spread during milking and some contagious bacteria spread outside of milking, but it's a useful starting point.

A good example of the difference between the two groups is the role of the dry cow period. Infections during the dry period come from environmental bacteria, so if you have a peak of mastitis in the first few days after calving then it is likely to be a problem with the environment, particularly the environment in the late dry period. However, if mastitis peaks 10 - 14 days after calving then a milking machine problem maybe more likely. It is important to stress that these are useful rules rather than laws, and individual farm investigation and bacteriology is required to confirm these suspicions.

Record keeping is important to be able to review possible problem cows and also highlight if there are any changes in the clinical incidence. Cell counting will provide data on both clinical and subclinical cases.

Environmental bacteria

The two most common environmental bacteria which cause mastitis are E. coli and Streptococcus (Strep.) uberis. Their relative importance has increased since the introduction of the five-point plan which focussed primarily on controlling contagious mastitis. Both bacteria can cause a wide variety of signs, ranging from inapparent subclinical mastitis to severe, toxic mastitis. Traditionally E. coli mastitis has been more commonly associated with toxic mastitis and a severely ill cow, but it is now also associated with a much milder form of the disease. Strep uberis is most commonly associated with relatively moderate mastitis with no systemic signs.

Strep dysgalactiae is the third most common environmental bacterium. It currently causes mastitis much less commonly than either Strep. uberis or E. coli because it can generally be effectively controlled by following the five-point plan. This is because spread in the milking parlour is more common for Strep dysgalactiae than the other environmental bacteria and because its most common site is teat skin, so post-milking teat dipping will reduce mastitis risk.

Contagious bacteria

The two most important contagious bacteria are Staphylococcus (Staph.) aureus and Strep. agalactiae. Strep. agalactiae bacteria used to be the most important cause of clinical mastitis and high cell count but because it is only found in the udder it is effectively controlled by the five-point plan. However, Staph aureus has been less well controlled by the plan and is the third most commonly isolated bacterium from milk samples sent to the VLA / SAC. Staph aureus can cause a wide variety of signs including a severe, toxic mastitis, but it is as a cause of high cell count problems that it is most commonly encountered. This is because Staph aureus often sets up a chronic, grumbling, walled-off infection deep in the udder. These can be very difficult to treat.

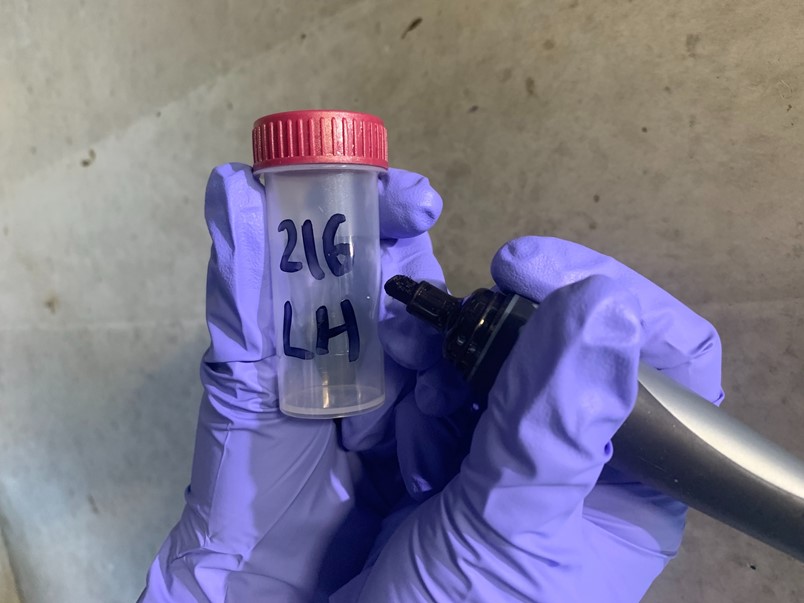

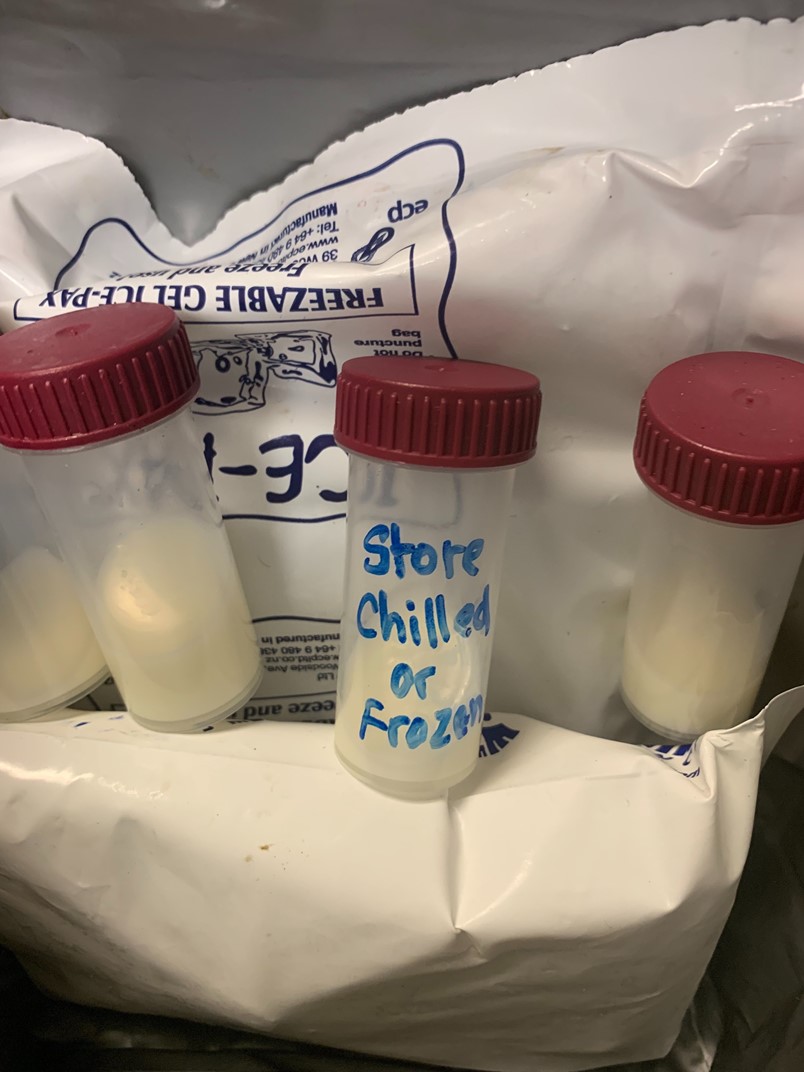

Fig 1 ( a - f below): Good sampling technique is essential if contaminated samples are to be avoided. Photos courtesy of Emma Redward

a: Wear examination gloves

b: Label the tube

c : Clean the teat end thoroughly

d: Avoid contaminating the lid

e: 5mL of milk is all that is needed

f: Get the milk cool as soon as possible after sampling

Sampling for bacteriology

Identifying which bacteria are causing the problem is an important part of any mastitis management plan. There are two key rules for sampling:

- Sample the cows that are representative of your problem. If the main problem is a high cell count without obvious clinical signs, then samples from clinical cases will be of little value and vice-versa. It is fairly easy to get representative samples if you have a cell count problem as you can sample 10 - 12 cows with high cell count and get useful results within 24-48 hours. However, if it is a clinical problem then many of the samples you want will be in the past as the cows have been treated, and you may have to wait a considerable period of time before you can collect 10 or so samples. It's thus a good idea to collect a sample from every cow that has mastitis before you treat her and to freeze it. So if you develop a problem, you have representative samples available with no waiting period.

- Take clean samples so that the only bacteria in the milk are those causing the mastitis. Aseptic technique is essential as many of the bacteria which cause contamination can also cause disease, which means that contamination can lead to misdiagnosis and frustration as well as increased costs. A good technique is summarised below:

Sampling milk for bacteria (see photo sequence above)

- Label the tube with cow and quarter

- Remove loose dirt, bedding etc. from the udder with a paper towel. Only wash the udder and teats if they are grossly dirty and start by cleaning the teat at the teat end. Always dry thoroughly

- Discard a few streams of milk

- Clean the teat end with an alcohol wipe for at least 10-15 seconds. If necessary use additional wipes until no more dirt is visible on the wipe or the teat end

- Take the cap off the sterile sample pot, keeping the open end facing downward

- Keep the pot at a 450 angle to avoid debris dropping into the pot; don't allow it to touch the teat end

- Discard a few streams of milk

- Collect up to 5mL of milk, 2-3 mL is usually sufficient

- Freeze or refrigerate if sending the next day.