The horn of the foot of the pig is designed to be protective. It has been stated that, in nature, the "foot is the hardware and the ground is the software" but in the indoor farming system these roles are reversed.

Furthermore, the high levels of productivity expected of the sow can be associated with defective horn growth, such that the protection afforded by the claw is incomplete. Also the high protein intake in growing pigs can encourage and distort horn growth in younger pigs damaging horn integrity. In either scenario, cracks can appear in the horn, which allows secondary environmental bacterial contamination to gain access to the sensitive tissues underneath. Proliferation of such contamination leads to abscessation within a sealed compartment, which ultimately swells and bursts producing what is commonly recognised as bush foot. (Fig 1)

The lateral (outer) claw is larger on each foot and the front limbs carry greater weight than the hind limbs. Despite this the front outer claws are not over-represented in incidence of bush foot - in fact the tendency is for lesions to occur more in the outer claws of the hind limbs.

Fig 1: Typical bush foot with abscess ready to burst above the claws.

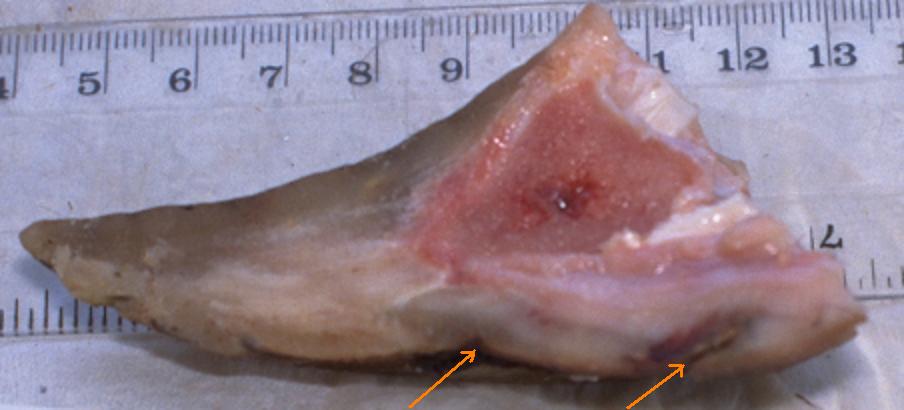

Fig 2: Sectioned overgrown claw highlighting defects in the weight baring surface through which infection can track.

Fig 3: Overgrowth and defective horn can predispose to secondary infection and bush foot.

Clinical Signs

In the early stages, there will be little other signs than a reluctance of the sow to put weight on the foot. She will act as if she is touching something hot. Over a few days, swelling may appear above the horn and the foot will be noticeably hot and painful. Unless action is taken, the developing abscess will infiltrate all tissues of the foot, including the joint cavity,tendons and bone, setting up a septic arthritis or osteomylitis and tendonitis. Ultimately, the pressure above the hoof will be so great that the skin will die off (necrosis) and the abscess will burst with pus and blood leaking out. The animal is likely to be 100% lame, be off food and reluctant to rise. Swelling of connective tissue may extend above the foot as far as the hock or elbow.

Precipitating Factors

Anything that causes damage to the claw can allow infection to penetrate the tissue between the horn and the digit (laminae).(Fig 2) Thus, rough abrasive flooring is heavily implicated, as can be worn slats. Outdoors, flint based land can be particularly harmful. Difficulty in rising if farrowing crates are too small or flooring is slippery will also risk horn damage. Sows that stand in persistently wet conditions, be they outdoors or in deep litter systems indoors, will tend to have softer horn, which is more prone to damage, and abrasion. Likewise, chemical damage from newly laid concrete can affect horn integrity. Fast growth and high protein rations tend to be associated with fast and distorted horn growth, which can be defective. (Fig 3). This is particularly relevant in replacement gilts. Excessive condition and weight in older sows can equally put strain on the horn structure and risk cracking.

Any environmental contaminant bacteria can gain access through horn defect to set up the infection. The most common organisms involved are Streptococci, Staphylococci or E coli, but a wide range of others, such as, Fusiformis and Trueperella (formerly Arcanobacter) pyogenes, may be implicated.

It is widely claimed that sows kept on straw during pregnancy have much lower levels of lameness than those kept on slats. This however is not necessarily true; as in all situations it is the nature and standard of a system and its management that determines how well a system works not the type of system per se. Where sows are kept in wet conditions or where scrap through passageways allow slipping and abrasion, high levels of septic laminitis can occur.

Systemic infections such as PRRS may act as trigger factors for the establishment of secondary bacterial disease either through the general debilitating effect of by more specific immune modulation.

In the pig, the very specific defects described in the cow - such as white-line lesions and solar ulceration - are not recognised; the whole condition generally is described as septic laminitis.

Treatment

Successful treatment of the affected individual depends on early recognition and aggressive antibiotic medication before deep-seated abcessation has occurred. Unlike the cow, which is equally prone to this type of lesion, the pus tends to be dry and is difficult to drain out of the foot, even with extensive debridement. It is important that the antibiotic treatment chosen not only is effective against the organisms involved but also has good penetration into the foot, particularly the bone and surrounding tissues and is given in sufficient dosage early enough. Your veterinary surgeon will advise but Lincomycin is one of the more favoured treatments due to good tissue penetration; it must, however, be administered for sufficient time to achieve success. A minimum of five days treatment is standard. Whilst it is good practice to establish bacterial cause and sensitivity to guide treatment in practice it is of little value - the delay in undertaking the tests will compromise recovery and the environmental nature of the organisms means that within a herd the actual bacteria causing a problem in one pig may not be repeated in others. Concomitant treatment with analgesics (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) is also indicated to improve comfort and welfare. Help to stand and gain access to food and water is vital. A sow so affected must be removed from the healthy competitive group and placed in an isolated hospital area on a clean dry bed, preferably straw based.

Unfortunately many cases are not recognised until it is too late to achieve success through treatment. These animals require on-farm euthanasia unless they can reach a state where pain and lameness is minimal and the animal can bare weight, rendering them suitable for "casualty" slaughter. In such cases, total condemnation of the affected limb would be expected. In practice with few casualty outlets available on farm euthanasia is necessary. In most commercial situations surgical treatment by paring and debridement of tissues or even digit amputation is not practical, economical or effective unlike the situation in the dairy cow.

Prevention

Prevention of the development of bush foot depends on identification and correction of any precipitating factors (such as rough floors, heavily contaminated wet conditions). This is a job that your veterinary surgeon can help to identify and correct.

Use of supplementary biotin in the ration can assist in reducing the incidence of bush foot. Classic biotin deficiency in sows is associated with horizontal cracks in the hoof wall, which are very rare. However, inadequate biotin and zinc in the diet are associated with soft horn, which is vulnerable to primary damage and infection. Supplementing the diet with extra biotin can appear to improve horn quality and, thus, reduce the risk of cracking that leads to bush foot. Your veterinary surgeon and nutritionist will advise on the appropriateness and levels required of such a treatment in each individual situation.

The levels required will depend upon the system on which the pigs are kept and the degree of damage seen.

The baseline levels of added biotin for sows housed on concrete would be in the order of 200-350 micrograms/kg of biotin (supplied by the addition of 10-16g/tonne of Rovimix H2 2% biotin premix (Roche)). 100mg/kg of feed of zinc is also standard - supplied in a soluble (available) form such as zinc sulphate - not the insoluble zinc oxide form. The zinc levels may need to rise further in outdoor herds on chalk soils - where zinc is bound up by calcium.

In problem herds the long-term biotin supplement level may need to rise three-fold or more (to 1000micrograms/kg plus) but even this may require 9-12 months to see clinical benefits. It is important that gilts receive these supplements in development to produce an adult with good horn integrity.

(In some studies, up to 3000 micrograms/kg feed of biotin has been added to give a more rapid response - i.e. within six months.)

The veterinary surgeon and nutritional advisor will work together to identify the needs of any particular problem herds.

Historically walking sows through foot baths has been tried but is not overly successful - particularly as sows may stop and drink the bath liquid. If formalin is used this would be expected to have fatal consequences.

Costs

The costs of septic laminitis can be measured in terms of welfare, treatment, lost production and loss of slaughter value. Many farms will suffer occasional cases of bush foot but "problem" herds have been seen in which 7%+ of all the sow population are affected over a year. In a 400-sow herd this equates to one case every fortnight.

Treatment costs per case can exceed £20 per sow and loss of cull value if the sow requires on-farm euthanasia (often after unsuccessful treatment) can cost £200 per case (including disposal) with the cost of the last unborn litter to add if the sow is pregnant.

Sow mortality data includes losses per herd, average around 5% but individual herds can be as high as 15% (annualised) of which 50% can be euthanased due to leg problems. Clearly, in such cases an accurate diagnosis is needed and where "bush foot" is identified remedial action is essential.

Acknowledgment

The author is grateful to Brian Vernon for assistance and advice regarding nutritional supplementation.