Output from the breeding herd is key to herd profitability.

When investigating sub-standard herd production it is often found that young sows over-represent breeding failure and in particular, problems are encountered in rebreeding the weaned gilt.

The syndrome termed "second litter drop" refers to the fall off in reproductive performance in sows being bred for their second litter and can be the cause of considerable production shortfalls within a herd. It may manifest in a number of ways but all have a common cause. The following may be seen:-

1) Second litter size (born alive) less than the previous (gilt) litter.

2) Delayed weaning to service interval in weaned gilts.

3) Reduced conception and farrowing rates in second litter sows compared to the rest of the herd.

Ultimately this leads to compromised lifetime performance and reduced longevity

Lameness or leg weakness associated with skeletal damage in the farrowed/weaned gilt is a further manifestation of the syndrome.

Clearly, accurate analytical records are needed to identify any of these features as being specific to this class of sows. Without such records it is impossible, for instance, to properly investigate a low herd litter size problem.

The root of all these problems relates to:

a) The growth, age and size of the gilt when first bred

b) The growth, nutrition and housing of the gilt during pregnancy

c) The workload done by the gilt during her lactation

Clinical inspection may reveal a marked loss of condition between farrowing and weaning. The difficulty arises because:-

1) Lactation creates very high nutrient demand.

2) The young gilt is also still growing and, this has a nutrient demand.

3) Gilt appetite during lactation may be limited compared to sows.

4) Gilts are often used as foster mothers to take extra piglets because the udder is likely to be complete and the teats small.

The target for age and size of the gilt at first service should be established. There has been considerable debate over this target and it may be that different genotypes have different targets. The aim is to maintain steady growth through the growing period from 50kg up to service (at say 125 to 135kg) such that the skeleton has the opportunity to grow with the muscle mass and allowing sufficient body fat to be deposited. Specialist gilt rearer diets are available and should be considered.

The housing conditions should also be considered with avoidance of slippery floors, overcrowding and poor ventilation.

Fig 1: Young gilts need space and non-slip floors.

Broad minimum targets for service of gilts - which are open to question - are 135kg live weight, 210 days of age and 20 mm of backfat. With modern genotypes the three characteristics may be difficult to achieve together and backfar is not routinely measured in commercial herds. Targets of 130 to 140kg often quoted at 220 to 240 days but modern thinking suggests weight at service is the key parameter and avoiding gilts getting too old may be more important. The other key parameter for serving gilts is to ensure they are not served before the second heat

Back fat is less important than overall body condition. Minimum body condition score should be 3 at service

Once served, it is important that the gilt continues its steady growth without adverse effects. Overcrowding, continual remixing of gilts and mixing of young gilts with pregnant sows all risk undermining the integrity and condition of the gilt at farrowing.

However, it is equally important to ensure that gilts do not get too fat or over condition as this will depress post farrowing appetite leading to greater weight loss (as well as risking high stillbirth rates and a greater tendency to savage the litter).

Fig 2: Mixing pregnant gilts with larger sows risks bullying and injury

To minimise the drain on resources of the gilt during lactation, the following points should be addressed:-

1) Do not get gilts in too good (fat) condition at farrowing. This will suppress appetite further.

2) Once farrowing is completed, reduce room temperature to 18-20°C, dependent upon piglet creep arrangements but avoid creating draughts.

3) Gradually build-up feed levels, over a 10 day period, with no pre-set maximum. Feed curves developed to suit the herd can be useful

4) Increase feed intake by:-

a) Feeding 3 times daily ensuring at least a 6 hour interval between feeds.

b) Supply ad libitum feeding . This should be not be given too early (ie from 7 days ) There is a risk of gilts stalling for a couple of days and if excessive intake occurs before this but such problems are not as prevalent with modern genotypes used in the UK as they once were.

c) Make a second round of feeding 20-30 minutes after the main feed and supply an extra 0.5-1kg food for any gilt (or sow) that has eaten up.

d) Add water to the food via a hosepipe or bucket - appetite increases on wet food, particularly if food is in meal form rather than pelleted.

5) Limit the number of piglets sucking on a gilt. Where problems occur, it helps to restrict gilts to suckling less than 11 piglets in the second half of a 4 week lactation. Care should be taken not to reduce the numbers being suckled too dramatically as this can have the effect of inducing oestrus whilst the gilt is still lactating. There is evidence to suggest that in order to ensure that all teats produce milk in subsequent lactations, the gilt should suckle as many pigs as there are teats available. If true this is only likely to be necessary for the first 7-10 days of the gilt's lactation thereafter numbers can be reduced.

6) Do not extend lactation length for gilts e.g. by using them as a late foster sow.

7) At weaning, do not mix weaned gilts with big old sows that will bully them away from food and cause injury. Pen weaned gilts separately.

8) Ensure gilts are healthy prior to breeding

9) In some problem herds where intractable problems occur the policy of "skip a heat" breeding for weaned gilts has been followed with marked benefits on both second litter performance and reducing early culling. The technique involves not serving the gilt on her first heat after weaning but delaying 3 weeks until the next heat period and is particularly useful in highly productive herds where gilt workload is high and gilts tend to lose body condition despite all other best efforts to avoid it. The net effect can be the economic and animal welfare benefit of increased longevity.

Leg Problems

The lactating gilt is still a growing animal and the growth plates at the ends of the bones will not have fused. Two specific clinical conditions are seen, particularly in the farrowed or weaned gilt, and can be linked to the syndrome of "second litter drop":

1) Osteomalacia - this involves insufficient calcification within bones so they become weak and prone to fracture. Lactation creates a drain on bone minerals and if not minimised or restored rapidly weakening of the bone will occur. (This condition can be more widespread affecting sows where major feeding errors occur).

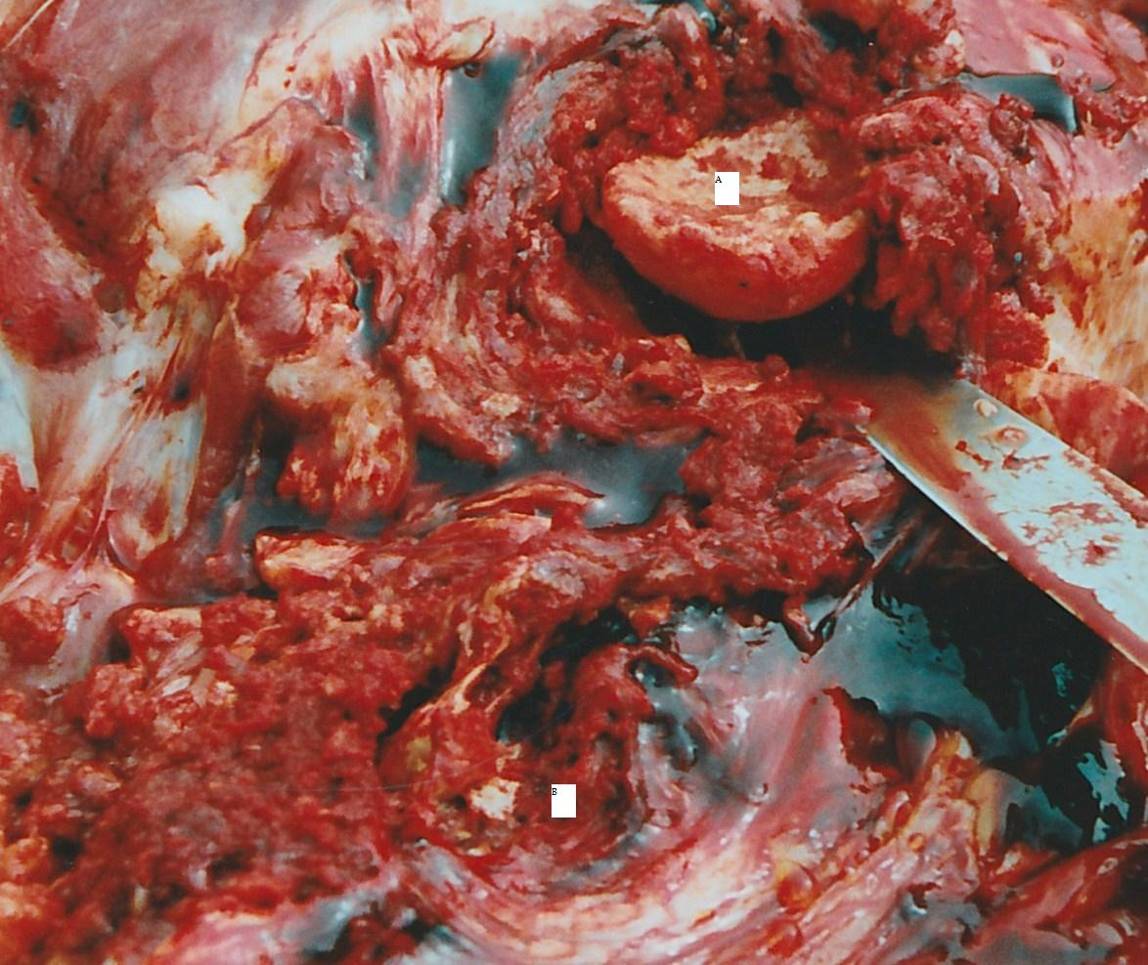

2) Epiphysiolysis - a severe manifestation of osteochrosis in which cartilage deformity as a result of problems during growth leads to separation of the femoral head (effectively a fractured hip) in the gilt under strain during or after lactation. Riding behaviour post weaning may induce sudden loss of back leg use which is irreparable and as such affected animals require euthanasia on farm. Such animals are in severe pain and are not suitable to be transported for slaughter.

Fig 3: Young gilt off legs suggestive of Epiphysiolysis

Fig 4: The head of the femur (A) pulled off from the bone (B) in a weaned gilt off legs due to Epiphysiolysis

Conclusions

In the modern pig herd, replacement rates (herd turnover) can be high - meaning young sows can make up a large proportion of the herd. Higher levels of productivity expected and achieved also place extra demands on the gilt, which, due to the increase in size of a mature sow - needed to produce a less mature slaughter animal at 5-6 months of age - has a less mature skeleton when bred.

Where problems exist with farrowing and weaned gilts - both in health and reproduction - the cause is likely to trace back to earlier life management in growth and lactation drain.