Introduction

The first two papers within this series provided a detailed outline of the causes of both short term (acute) and long term (chronic) respiratory disease in pigs and the various factors which trigger problems. The relationship between the causative organisms and the pigs' immune system was explored. In this third paper the aim is to develop some of these concepts to be able to understand how the environment, (both physical and social) plays a critical role in disease development. In the second part we will look at pharmaceutical control of long term disease within a population both by use of immunological products (vaccines) and antibiotics.

Environment

As a general principle, the requirements of the growing pig for health can be summarised as; clean buildings, clean air, clean water and food and a temperature that maintains the pig within its required range - known as thermo-neutrality.

Hygiene

The cleanliness of a building is integral to health generally. The greater the level of contamination by pigs, whether the result of faecal or aerial excretion, the higher the level of microbes within the building, increasing the challenge either to the existing population or to those pigs following on.

The ideal situation might be deemed to be an isolated room or building which is filled in one go with pigs of the same age; the pigs remain within that group for the requisite time during which contamination is removed (e.g. via slats or physical removal plus fan ventilation) before all exiting at the same time allowing full cleaning, washing, disinfecting and drying of the building before the next batch enter. This is the classic All In All Out concept (AIAO).

If any of these features fails then hygiene breakdown and disease can result. Examples will include:-

1) Filling the room with mixed ages of pigs. As detailed in the first paper of this series, growing pigs go through a challenge, multiplication, excretion and immune development cycle (with or without disease) as they grow. This means that older pigs act as a source of infection for younger pigs exacerbating disease.

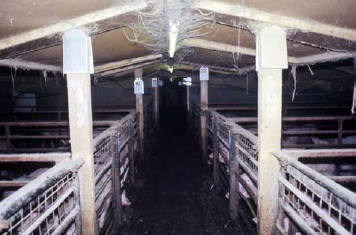

2) Rolling populations - permanently occupied buildings in which young pigs enter regularly and older pigs are removed (e.g. weekly) creates a constant cycle of disease with the naïve young pigs "feeding the fire" of infection. Scrape through dunging systems exacerbate the situation, encouraging spread of disease whilst permanent occupation of the building often procludes sufficient cleaning.

3) Cleaning failures - even when AIAO policies are followed a failure to clean, disinfect and rest buildings between groups undermines any benefit.

Aerial Pollutants

Pigs and their excreta generate a range of aerial pollutants which can damage the respiratory tract or impede appetite leading to chronic disease.

Fig 1: Naturally ventilated straw yards for finishing pigs can lead to ammonia build up in hot weather, exacerbating respiratory disease.

Ammonia

In the paper on Acute Respiratory Disease (Paper I) a broad outline of the protective mechanism of the respiratory system was provided including the escalator system for removing mucus (phlegm). This depends on cells lining the airways which move the escalator. High ammonia levels paralyse these cells and so contaminated mucus gets trapped in the lung allowing microbes to multiply.

In cold weather mechanical air movement may be reduced (to maintain temperature) and in hot weather particularly in naturally ventilated straw yards the ammonia levels can increase explaining the often seen respiratory disease in midsummer in yards (Fig 1).

Dust

Inhaled dust gets trapped in the nasal chambers and on the mucus escalator. If excessive, it can overload the escalator - thickening the mucus - making removal difficult thus leaving inhaled microbes in the lung, some of which will be carried on dust particles. Thus, dusty conditions (including those in straw yards) can exacerbate respiratory disease (Fig 2). In addition, dust will contain foreign protein (allergens) which can damage the structure and the immune mechanism of the lung increasing vulnerability to infection.

Fig 2: High dust levels affect lung clearance mechanisms exacerbating respiratory disease.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

Raised CO2 levels are soporific and will reduce feeding activity. They are often indicative of poor aerial quality and may well rise in parallel with ammonia levels.

Reduced feed intake especially in cold weather (when fans may not be removing foul air) can have a long term stressing effect on the pig increasing susceptibility to disease.

Temperature

All pigs exist within a thermoneutral zone, i.e. a temperature range, in which their body temperature can be maintained with minimal effort and energy expenditure. Outside of this range - which will be determined by age/size, group size, insulation levels and bedding, feed levels and air flow - pigs expend more energy. Over a prolonged period (6-12 hours or more) this can increase susceptibility to disease.

There is a very delicate balance required between temperature control and air flow - which itself will be influenced by insulation levels and heat provision - to provide satisfactory conditions for pigs. Building provisions must be reviewed as part of any long term health control programme.

Group size and stocking rates

As a rule of thumb, the more pigs there are within a given airspace (i.e. greater group size) the greater will be the generation of microbes within the population and the greater spread. This will be exacerbated by high stocking density i.e. the number of pigs per square and cubic metre in the building and mixing of ages and sources.

Statutory minimum floor space requirements exist (Fig 3) but the key to these figures is that they are LEGAL MINIMUM levels not optimum. Practical stocking will be determined by building type e.g. pigs in fixed straw yards need approximately 2.25 times the space that pigs in fully slatted accommodation require.

The unobstructed floor area available to each weaner or rearing pig reared in a group must be at least-

(a) 0.15 m² for each pig where the average weight of the pigs in the group is 10 kg or less;

(b) 0.20 m² for each pig where the average weight of the pigs in the group is more than 10 kg, but less than or equal to 20 kg;

(c) 0.30 m² for each pig where the average weight of the pigs in the group is more than 20 kg but less than or equal to 30 kg;

(d) 0.40 m² for each pig where the average weight of the pigs in the group is more than 30 kg but less than or equal to 50 kg;

(e) 0.55 m² for each pig where the average weight of the pigs in the group is more than 50 kg but less than or equal to 85 kg;

(f) 0.65 m² for each pig where the average weight of the pigs in the group is more than 85 kg but less than or equal to 110 kg; and

(g) 1.00 m² for each pig where the average weight of the pigs in the group is more than 110 kg.

Fig 3 from The Welfare of Farmed Animals(England) Regulations 2007 Schedule 8

Where chronic respiratory disease occurs it may be appropriate to reduce stocking density by anything up to 30%. However, such a reduction obviously incurs a financial penalty and must be carefully costed out. Furthermore, in cold weather the balance between temperature maintenance, air flow and stocking rates will often require some compromise.

Hospital Pens

A full discussion of hospital pen requirement is beyond this paper but where disease occurs it is vital that facilities exist to deal with compromised pigs. The same principles apply here as to the mainstream accommodation i.e. warmth, hygiene, AIAO, but extra care is needed as these represent the most diseased pigs and have the greatest danger to healthy pigs. Returning hospital pigs to the mainstream can be a high risk strategy as many sick pigs are chronically affected and act as generators and sources of infection. As a rule of thumb, do not return sick pigs to the mainstream system.

Vaccination

The idea of vaccination is to expose the pig to a controlled dose of a particular harmful organism (which has been altered to reduce risk of it causing disease) to allow the young pig to develop immunity such that it is protected against that infection when it meets it later in its growing phase. Whilst some diseases of growing pigs can be controlled by vaccinating the sow - relying on transfer of immunity to piglets soon after birth - most of the respiratory pathogens are controlled by direct vaccination of the piglets. Table 1 lists those diseases for which vaccines are currently available.

Unfortunately at present, even though some farms require multiple vaccinations, complex combination vaccinations (such as those available for cattle, dogs and cats) are not available, but they are slowly being developed.

A carefully drawn up programme is required for each individual farm and care is needed when more than one disease requires control as it is often not appropriate to give 2 different vaccines simultaneously. This is particularly relevant with PCV2 vaccines.

Some general rules regarding piglet vaccines and their administration can be drawn up:-

- Store unused vaccines in a fridge (2-8°C)

- Discard part used bottles

- Only use clean equipment to administer

- Adhere to product licence advice or veterinary advice (if different) regarding dose and timing of vaccine administration

- Do not combine vaccines in the same syringe

- Only vaccinate healthy animals

- Vaccinate young piglets (slaughter generation) in the neck rather than the ham

Vaccination against specific diseases e.g. Enzootic pneumonia does not protect against all types of pneumonia. It is always necessary to undertake a proper diagnostic investigation and tailor vaccine provision to the specific farm requirements. The monitoring programme outlined in the second paper in this series (CRD Control Part I) must then be continually used to monitor the effectiveness of the vaccine and adjust the programme where necessary.

By way of example, abattoir examination (under BPHS) identifies Enzootic Pneumonia type consolidation in a known infected farm, with an SEP score of 8. Vaccination is applied to piglets at weaning (using a commercial Mhyo vaccine) and 12 months later the SEP score has reduced to 2. On farm data would be expected to show an increase in growth of c45gms/day between 30-100kg reducing days to slaughter by 5 days saving 8 kg of feed i.e. £1.18/pig.

Table 1

Respiratory Pathogen Vaccines for pigs

1. Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (Enzootic Pneumonia)

2. Porcine Reproductive Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS)

3. Porcine Circovirus Type II (PCV2)

4. Haemophilus parasuis (Glässers Disease)

5. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae*

6. Strep suis*

7. Pasturella multocida type D (Atrophic Rhinitis)

8. Aujeszky's Disease**

*only available under Special Import Certificate

**applies to Northern Ireland only

Medication

In many cases vaccination is either not possible, electively rejected or proves insufficient to control the Porcine Respiratory Disease Complex (PRDC). In these cases substitution or supplementation with in-feed or water medication is necessary to control bacteria or Mycoplasma components. Antibiotics are not effective against viruses.

A number of strategies can be applied:

1. Long-term preventative medication, via feed, at levels which will suppress bacterial growth. In continual production farms (e.g. breeder/feeder) this may require medicating all pigs between certain ages to cover the risk period. In this way the feed will be permanently medicated for that duration. This is to be avoided as a permanent strategy where possible.

2. Snap treatment via feed or water for 5-14 days depending on product, in response to a breakdown or escalation of disease.

3. Strategic medication by injection, water or feed at high levels for short duration in anticipation of a problem. For example, if respiratory disease is known to occur at 9 weeks of age, 7 - 10 days after the move into 2nd stage accommodation, then medication at the move is appropriate.

4. Reception medication. Similarly to 3 above, newly arrived pigs onto a finishing site may receive 2-3 weeks of medication to cover them over the stresses of transportation, mixing, change of feed etc. It is possible to use high levels of certain medicines e.g. Tilmicosin (Pulmotil: Elanco) to virtually eliminate certain pleuropneumoniae and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae) but this will tend to leave a naïve population and observation of strict biosecurity is necessary to avoid a subsequent primary breakdown.

The choice between medication and vaccination or a combination of the two will depend upon:

1. The microbial profile of the herd.

2. The age of the pigs affected.

3. Availability of vaccines.

4. Role of viruses in PRDC to which antibiotics have no effect.

5. Cost balances. Individual vaccines for various respiratory infections will cost anything from 60p - 130p per dose (60p - 260p per pig depending on vaccine and single/double dosing protocols).Vaccination for Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae, PRRS and PCV2 can add £3 to costs. In-feed medications are equally variable. Examples might include:

a) Two weeks medication for 30kg pigs with Pulmotil (Elanco) costs around £2 per pig.

b) CTC (Aurofac:Alpharma) at 400ppm for 4 weeks for pigs from 12-16 weeks costs about 40p per pig.

c) Tylosin (Tylan Premix:Elanco) for finishing pigs 13 - 25 weeks @ 100ppm costs about £2.50 per pig.

The added complication in using in-feed medication is the necessity to observe withdrawal periods prior to slaughter. Veterinary advice will take this into account when prescribing.

Where long-term disease problems occur and control costs have become excessive, partial or complete depopulation with appropriate cleaning and disinfection before repopulation may be appropriate. The cost and consequent benefits must be carefully balanced against the risk of subsequent disease problems and appropriate alteration to buildings and system management is an important component of such programmes.