Introduction

In the first paper of this series, emphasis was given to the breakdown in a group of pigs with a new disease causing an acute outbreak of pneumonia and other respiratory ailments. Here, the aim is to concentrate on more long standing (chronic) enzootic (endemic) disease, which arguably, in the UK pig industry, produces even greater financial loss than sudden one off outbreaks, being a very common problem.

The terms acute and chronic must be clearly understood. Acute disease appears rapidly, causes its harm and provided it is not rapidly fatal leads to speedy recovery. Chronic disease however, represents a long-standing problem that leads to prolonged or permanent damage to the pig, from which it may never satisfactorily recover.

In the context of a dynamic population or a large fixed population, chronic illness is usually associated with infections which are permanently present in that population (enzootic), affecting pigs as they reach a susceptible age group. Within that group some individuals may suffer acute signs of pneumonia (and die or quickly recover) whereas others may be left chronically damaged. It is this long-standing, continual disease problem with which we are concerned here.

Causation

Unlike the sudden acute outbreaks of disease, which typically may be caused by a single agent (e.g. Swine influenza), chronic population disease is usually more complex with a wide combination of agents often acting synergistically. Table 1 highlights the range of organisms usually associated with respiratory disease in the UK.

|

Table 1: Major Infectious Causes of Chronic Respiratory Disease |

|

Porcine Reproductive & Respiratory Disease (PRRS virus) |

|

Swine Influenza (SI) virus |

|

Porcine Circovirus type II |

|

Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

|

Porcine Respiratory Coronavirus |

|

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae |

|

Mycoplasma hyorhinis |

|

Haemophilus parasuis |

|

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae |

|

Actinobacillus suis |

|

Streptococcus suis |

|

Pasteurella multocida |

|

Bordetella bronchiseptica |

|

Arcanobacter pyogenes |

|

Lungworm & Migrating worm larvae |

The disease that results from a combination of these agents is referred to as Porcine Respiratory Disease Complex (PRDC) and whilst any or all of the agents listed in Table 1 may be involved, for the purpose of this paper the most common will be referred to. Furthermore, some of these agents typically act as primary pathogens - capable of causing some harm on their own - whereas others only act as secondary diseases, taking advantage of damage done by the primary agents. However in PRDC there are complicated interactions occurring which can make it difficult to identify which agents are most significant.

|

Table 2: Important Primary and Secondary Pathogens of the pig lung. |

||

|

Primary Agents |

Primary or Secondary Agents |

Secondary Agents |

|

PRRS virus |

Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae |

Pasturella multocida |

|

PCV2 Virus |

Actinobacillus suis |

Streptococcus sp. |

|

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae |

|

Arcanobacter pyogenes |

|

Haemophilus parasuis |

|

|

Development of Disease

In order to understand why complex respiratory disease occurs repeatedly within a herd it is necessary to understand the dynamic behaviour of the immune system and its interaction with potential pathogens.

In a typical breeder-feeder farm, it will be assumed that a range of primary and secondary agents is present. In reality, most herds in the UK are infected with PCV2 virus and Haemophilus parasuis (the cause of the well known Glasser's Disease). Enzootic pneumonia - caused by Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae - is believed to be present in approximately 75% of UK herds whilst PRRS virus may be present in up to 50% of herds.

The secondary agents are often commensal organisms i.e. organisms - usually bacteria - which are normally present in the population and only cause harm consequent upon the primary agent or agents acting to open the door. It should be noted that with many of these agents, both primary and secondary, there are many different strains and this has implications for the mixing of different sources of pigs (e.g. as weaners or indeed the introduction of replacement breeding stock).

Within the infected herd, the breeding animals are likely to have encountered the various agents earlier in life and whilst they may carry the organisms and periodically excrete them, they are largely immune with protective antibodies present in the bloodstream.

When piglets are born they acquire protective immunity from the sow (Maternally derived antibody, MDA) from colostrum, provided they suck adequately in the first 6-12 hours of life. This gives them temporary protection before they encounter field infection and develop their own active response.

This MDA will decay with time leaving the young pig exposed to infection and disease. If the exposure to the primary agents is only a trickle of infection, then the young pig can develop its own immunity without harm occurring. However, if a heavy infection occurs it may overwhelm the pig leading to disease. The level of contamination of secondary agents will determine the severity of disease.

The duration of persistence of MDA will depend upon:-

1) The volume and timing of colostrum taken by the piglet - the more and earlier the better

2) The concentration of antibodies in the colostrum - in general sows have higher concentrations of antibodies than gilts

3) The agent to which the antibodies relate - e.g. MDA to PRRS virus lasts up to 5-6 weeks, to M. hyopneumoniae 8-10 weeks, and to H. parasuis 2-4 weeks.

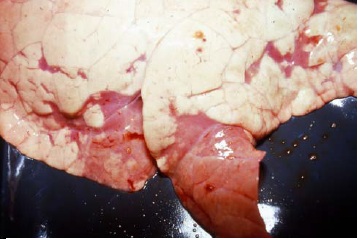

Fig 1: Consolidation of the lung typical of Mycoplasma infection (Enzootic pneumonia)

Fig 2: Pleurisy is a common consequence of PRDC

Fig 3: Chronic respiratory disease in a young pig

4) The level and age of challenge to the piglet - field infections "mop up" MDA and leave the pig exposed to further infection.

It can thus be seen that immunity to different agents will fade at different ages and importantly the immunity in individuals will fade at different ages. The larger the population the greater will be the diversity. Once immunity fades in sufficient number of pigs the sequence of infection, colonisation, replication and excretion of the agents will increase leading to disease.

The primary agents will create damage in the lung (e.g. PRRS virus incapacitates the natural immune cells in the lungs leaving the lung vulnerable to further insult either by other primary agents or secondary bacteria). Pneumonia and/or pleurisy (inflammation of the lining surface of the lung leading to adhesions to the chest wall) will result. The complex microbial interactions mean that each of the primary agents can help the other become established.

Diagnosis and Monitoring

It is possible to identify when a range of agents are active in the young population by cross-sectional blood testing. This involves sampling a number of pigs in each age group simultaneously (e.g. 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20 weeks of age). The point at which the blood samples turn positive for antibodies indicates that infection occurred in the 2-4 weeks prior to the test. Such a technique is useful to assess the behaviour of PRRS virus in a herd but does not necessarily mean that it has caused harm - just that the virus was active.

Accurate diagnosis can only be achieved by post mortem examination of affected pigs prior to treatment. The gross picture may be strongly indicative of the cause (e.g. M. hyopneumoniae Fig1) but laboratory tests including bacterial culture, PCR examinations (looking for the DNA of specific organisms) and histopathology on lung tissue are necessary to confirm each organism's role. Long standing cases of pneumonia may become overrun with secondary bacteria as the primary agent disappears. Early cases must be used for investigation purposes.

Where PRDC is known in the herd, as well as monitoring the clinical picture and recording the numbers, duration and severity of clinically disease pigs, the overall herd picture can be routinely monitored by examination of pigs in the abattoir.

Many pigs are slaughtered with lesions in their chests, such as consolidation of lungs (indicative of Mycoplasma infection/Enzootic pneumonia), abscessation and pleurisy. By examining and scoring batches of pigs at regular intervals, a picture can be drawn up of changes over time - both improvements and degeneration. By having acceptable standards set, this will allow appropriate on farm intervention (to be discussed in the next paper) to be introduced and for this action to be assessed as to its beneficial effect.

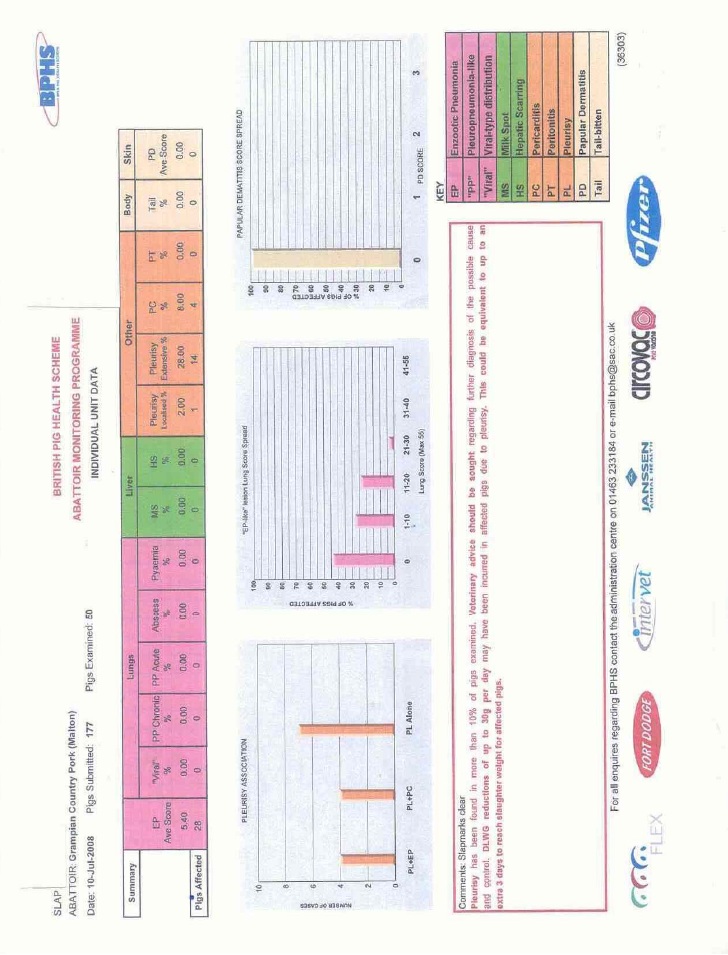

The British Pig Health Scheme operated under the auspices of BPEX provides a cost effective monitoring programme both nationally and for individual farms run by veterinary surgeons, to which all producers of slaughter pigs are encouraged to subscribe.

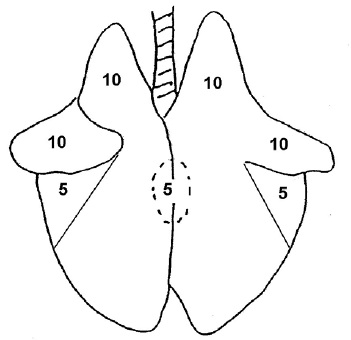

By way of example, consolidation of lungs is scored out of 55 with the 7 lobes of the lungs afforded an appropriate score dependent on significance of each lobe to enzootic pneumonia. Thus the anterior lobes are more likely to be affected and thus warrant up to 10 points each (see Fig 4 ). The average score of a batch of 50 pigs provides an indication of the severity and consequences of the disease.

Fig 4: The basic 55 scoring system for Enzootic pneumonia type consolidation.

Fig 5 (on next page) is an example of the report derived from an abattoir inspection of a batch of pigs under the BPHS, sowing the various types of pathology detected and recorded.

Costs

Studies have shown that 10% of the vulnerable (i.e. scored) lung damaged will impede growth of the pig between 30 and 90kg by 40gm/day adding between

4-5 days to slaughter age. Thus an average score of 5.5 will mean that every pig requires an extra 7kg of food to reach finishing weight at a cost of £1/pig.

This would equate to a very modest level of clinical disease in the herd.

A herd with a significant clinical problem requiring ongoing treatment and causing death or producing unmarketable pigs might have an average score of 14. In a 500 sow breeder feeder farm, each pig will incur a cost of £2.50 in extra feed and when coupled with mortality and ongoing medication costs can take the annual cost of disease up to £50,000.

Likewise pleurisy, which is difficult to detect in the live pig, also slows growth and it is claimed that the presence of pleurisy can represent a reduction in affected pigs of 30gm/day. If 20% of pigs slaughtered were affected, this would give an overall cost penalty per pig produced of 15 pence in addition to the costs of pneumonia, treatment and unsaleable pigs.

Fig 5: An example of the report derived from an abattoir inspection of a batch of pigs under the BHPS, showing the various types of pathology detected and recorded.

Conclusion

PRDC is common in the UK pig herd and results form complex interaction between viruses, Mycoplasms and bacteria. The dynamic population typical of a breeder feeder enterprise is particularly vulnerable although disease is common in split site systems, particularly where pigs arise from more than one source or ages are mixed.

Disease levels can be monitored by both on-farm recording and abattoir monitoring which will provide a base line for assessing both the need and the cost effectiveness of on farm intervention to reduce losses.