Introduction

Respiratory disease in the form of bronchitis and pneumonia is one of the most common presenting syndromes seen in growing pigs. The aim of this module is to provide background information on development of respiratory disease from which we can develop an understanding of necessary methods of control.

In this first paper of three, the aim is to briefly examine the anatomy of the respiratory system of the pig and how that is then affected by disease.

The aim will then be to study the causes of acute (i.e. sudden onset, short duration) pneumonia in pigs, how they are presented (clinical signs) the damage that is done to the lungs, treatment and control.

Unfortunately, in commercial pig farming, respiratory disease is often a very complex syndrome with multiple causes producing long standing (chronic) herd problems. This will form the focus of the 2 subsequent papers in the module.

Anatomy and Function of the Respiratory System

Fig 1: Outline of pig respiratory tract

Of necessity, the respiratory system is exposed to the outside air and thus any particles, gases and harmful organisms that are present in the air can be sucked into the lungs where they can do damage. (Additionally harmful organisms can reach the lungs via the blood stream). The respiratory system thus has a number of features aimed at reducing the chances of harmful substances reaching the lungs (Fig 1).

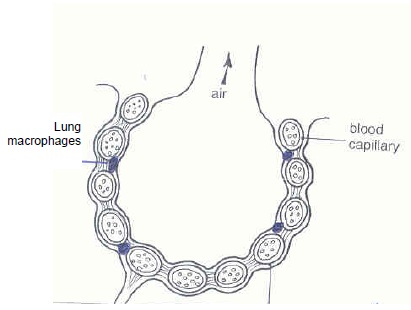

At the upper end of the respiratory tract the nasal chambers act as a filter, humidifier and warmer of incoming air. The tonsils act as sentries, attacking any organisms that may settle on them. The larynx acts as a further large filter before air reaches the lower respiratory tract. This can be viewed as akin to a tree with progressive branches getting smaller and smaller, until the main oxygen exchange area of the lung is reached (Fig 2). Within the airways (trachea, bronchi and bronchioles), the surface is lined with a film of mucous (jelly) which is continually moved upwards (in the form of an 'escalator' to form phlegm) to be swallowed or ejected. Dust and microbes can stick to the film and then be cleared from the system. Finally, within the lung tissues are smaller chambers (alveoli) in which very small blood vessels (capillaries) are in very close contact with the air allowing its absorption into the blood stream. In this area immune cells can attack any invading particles (whether inert or living) in an attempt to ward off damage (Fig 3).

Fig 2: Lower respiratory tract

Fig 3: Lung alveolus

Respiratory disease will result where:-

a) Particle inhalation overloads the filters and cleaning system

b) Damage is done to the filters and cleaning system by polluting gases of microbes, limiting clearance

c) The immune system itself is attacked or compromised

d) Infectious agents (bacteria, viruses etc) are too powerful for the defence mechanism

Most respiratory disease arises as a result of one or more of these problems.

Furthermore, the site of damage within the respiratory system will determine the clinical signs seen. If the airways are attacked, damaged or irritated, cough will be the predominant sign. If the lower oxygen exchange area is damaged, thickening will result, limiting oxygen absorption, producing laboured or compromised breathing (dyspnoea). In practice, most clinical cases of respiratory disease combine both features to a greater or lesser extent.

Infectious Causes of Respiratory Disease in Pigs

Table 1 lists the range of microbial organisms most likely to be associated with respiratory disease in pigs.

In this first module we will look at the effects of single infection causing acute disease in individuals and groups of pigs using, as examples, one virus (Swine Influenza - SI) and one bacteria (Active pleuropneumoniae - AcPP).

Table 1: Major Infectious Causes of Respiratory Disease

|

Porcine Reproductive & Respiratory Disease (PRRS virus) |

|

Swine Influenza (SI) virus Porcine |

|

Circovirus type II Aujeszky's |

|

Disease virus * Classical Swine |

|

Fever virus * Respiratory |

|

Syncytial Virus Porcine |

|

Respiratory Coronavirus |

|

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae |

|

Mycoplasma hyorhinis |

|

Haemophilus parasuis |

|

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae |

|

Actinobacillus suis |

|

Streptococcus suis |

|

Pasteurella multocida |

|

Bordetella bronchiseptica |

|

Lungworm & Migrating worm larvae |

* not present in GB as at 01/01/09

Clinical Signs

The clinical signs of respiratory infection will to some extent depend upon the organism involved and its target tissue, the age and susceptibility of the pig and the level of the challenge experienced. However, a common series of clinical signs can be drawn up. The pig will tend to be inappetant and depressed, often lying separate from its pen mates. There will be a cough, which may require disturbance of the pig to induce, and breathing rate and intensity will increase. In severe disease, abdominal breathing ("thumping") will be evident. There may be cyanosis (blue discolouration) of the ears and as the severity increases the pig may lie out on its side and be unwilling or unable to get up.

Rectal temperature will be raised. The normal temperature of the growing pig is 38.5°C - 39.5°C but in acute respiratory disease this can rise above 42°C. (note; normal human temperature is 37°C)

Immediately prior to death - especially with AcPP infections - blood stained froth may appear from the mouth or nostrils. Most of the organisms listed are capable of producing acute disease in individuals. However, here we will concentrate on two organisms that cause acute outbreaks in groups of pigs.

Actinobacillus Pleuropneumoniae

1) Clinical Presentation

An outbreak of AcPP in a group of growing pigs will typically be of sudden onset and the first sign may often be the appearance of dead pigs in the pen - possibly with frothy bloody nasal discharge. The rest of the group will show a range of signs with some severely infected and recumbent with laboured breathing, others with a cough but willingness to move around whilst others are apparently normal.

If untreated, the disease will gradually spread through the group, with further pigs dying over a few days. Spontaneous recovery, whilst possible, is unusual except with the mildest strain of AcPP. Weight loss will become evident in individuals less severely affected, total feed use will decline and the disease will progress to leave chronically damaged pigs which may require euthanasia. If they manage to achieve slaughterable weight, pleurisy - where the lungs stick to the wall of the chest - and underlying pneumonia will be evident.

2) Post Mortem Findings

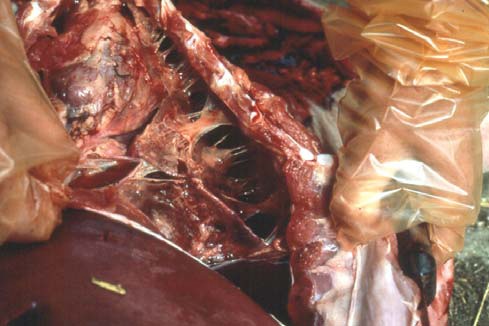

Acute AcPP infection causing death presents a very typical picture of damage to the lung tissue (Fig 4). The lung will appear hardened and haemorrhagic (full of blood) with a film of pleurisy over the surface.

(There may also be tags of material (fibrin) evident in the abdomen). In some cases only one lung may be affected and then there will be a modest amount of fluid accumulating in the chest cavity - usually blood stained.

In more longer standing cases the pleurisy becomes organised such that the lungs stick to the chest (Fig 5) and typical 'core' lesions are evident in the lung tissue. Ulceration of the stomach with bleeding may be seen as a complicating factor.

3) Treatment

If not rapidly treated, acute AcPP in a group of pigs can kill up to 50% with many others never fully recovering.

Appropriate antibiotics must be applied (ceftiofur is particularly effective) but it is the route of administration which is critical. Appetite will be so depressed that use of feed medication is of no value in acute disease - a fault which would be exacerbated by delays in preparing medicated feed. However, pigs that are sick with AcPP will not drink either and the only effective way of treating sick pigs is by individual injection at the appropriate full dose (as per veterinary advise).

This should be followed up by water and feed medication which will minimise the spread of disease within the group and prevent further new cases. Very sick pigs will require assistance to drink if they are not to become dehydrated.

Fig 4: Acute AcPP lungs at post mortem examination

Fig 5: The chronic (long term) effects of AcPP include pleurisy.

One of the surprising features of acute AcPP disease can be the response to treatment. Even the apparently sickest pigs with the highest temperatures can recover within 6 hours of appropriate individual treatment.

4) Prevention

Acute AcPP occurs in groups of susceptible pigs when they meet infection. In batch finishing systems, mixing sources of pigs on a site is a classic way of triggering outbreaks as is placing pigs into an infected environment. Single sourcing and attention to hygiene (including during transportation) and biosecurity are central preventative measures.

The organism will not spread very far on the wind (probably no more than 400metres) and the main source of introduction is infected pigs.

In the continual flow of a breeder feeder farm, pigs can reach an age where maternally derived immunity is lost and they become susceptible to disease. In this situation continual acute disease is seen weekly as each group attains the susceptible age. In such cases preventative in-feed medication can be appropriate or a vaccination strategy can be applied - normally involving a 2 dose killed vaccine given at least 2 weeks prior to the danger time. Over the years both autogenous vaccine (ie those made specifically for an individual farm from its own isolate of AcPP) and commercial vaccines have proved effective but tend to be strain specific. Ideally a vaccine covering a range of strains should be used to allow for "mutation" or strain shift.

Fig 6: Acute pneumonia in a single growing pig.

Swine Influenza

1) Clinical Presentation

As with AcPP, acute Swine Influenza has a sudden onset but due to a very short incubation period (24 hours) a typical outbreak may present as a whole building/yard affected. In the classic cases the building will appear quiet with some coughing with pigs not reacting to people. When disturbed, widespread continuous rasping coughing will occur.

Appetite in the group can drop to virtually nothing. Rectal temperatures will all be raised above 41°C. In uncomplicated Swine Influenza death is rare.

The presented pattern is likely to persist for 2-3 days before pigs spontaneously recover. Where there are several buildings within a farm, the disease can pass through in waves with groups affected sequentially.

In recent years milder strains of SI virus have appeared in which the clinical picture is less severe and specific, but unless complicated with other agents, long term damage to individuals is rare although age at slaughter will be extended by 7 days.

SI can act as a trigger for other acute respiratory disease - particularly AcPP - and in such cases action as described above is necessary.

2) Treatment

In uncomplicated SI outbreaks, treatment of pigs is both ineffective and unnecessary. There are no anti-viral medicines available for pigs and the spontaneous recovery renders treatment uneconomic and pointless. Warmth and clean air are key to a quick recovery. However, where there is complicating bacterial disease or a known risk of secondary infection, mass treatment via water or feed - of appropriate selected antibiotics - applied as the group begin to recover from SI infection may be appropriate.

SI may be involved in, but not actually recognised as triggering, an acute AcPP outbreak which should be dealt with as described for that disease.

3) Prevention

SI viruses are believed to be capable of spreading many miles on the wind and outbreaks will occur sequentially on farms within an area. There is little that can be done to stop its spread.

The epidemic nature of the disease would render routine vaccination of questionable cost effectiveness and, to date, no vaccines against the range of SI strains seen have been made available within the UK. Moreover, SI viruses have a strong capacity to change (shift and drift) meaning that there is always a risk that any vaccine produced would soon become ineffective