The ability of the sow to adequately rear her litter is key to successful breeding herd productivity. Lactation failure is a common problem affecting the whole or part of the udder.

The failure of a sow to produce milk during lactation is termed agalactia. In many cases, this is confused with mastitis and, whilst occasionally agalactia may result from specific infection and inflammation (i.e. mastitis) of the udder, it is quite rare. This article will concentrate on those circumstances where there is a total lactation failure or reduction in milk production as well as addressing the conditions that lead to individual mammary gland failure.

Fig 1: A full udder during mid lactation a is the aim. If it occurs too early it can lead to congestion and agalactia.

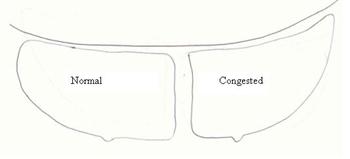

Fig 2: Pictorial cross section of normal and congested mammary tissue. Note: elongation of lateral edge which can be palpated as a hardening of udder tissue

Fig 3 : Actinomycosis of the udder post weaning

1) Failure of udder tissue to develop

Seen primarily in gilts and recognised in the period immediately leading up to and immediately following farrowing as a failure of the mammary tissue to enlarge so there is no functional milk producing tissue. This can result from:-

a) Inadequate nutrition - particularly gilts that are maintained on a low protein, low lysine diet at basal levels right up to farrowing. In group fed sows, the same can occur if individuals are bullied out of feeding in late pregnancy.

b) Toxins. Ergot poisoning is a classic cause of inhibition of mammary growth but other mycotoxins can have similar effects. Feeding mould affected food or bedding should be avoided at all times.

c) Lack of water supply.

2) Failure to produce milk at farrowing

If sufficient udder tissue has developed, colostrum and milk will be produced, unless there is a major limit placed on the sow. Inadequate water is the most likely cause of failure.

3) Initial lactation with later agalactia

The primary stimulus for continued milk production is removal of milk by the suckling piglets. Anything that interferes with sucking (weak or premature pigs born, severe piglet disease) will reduce the stimulus to produce milk and can lead to agalactia.

Similarly, a severe limit on nutrition can simply lead to a failure to produce milk as a result of protein and energy deficiency.

One of the most commonly seen cause of agalactia in sows arises as a result of excessive colostrum/milk production around farrowing. Even a strong, healthy litter will not remove all this milk, leading to pressure build-up in the udder and resulting tissue damage that limits milk production. In these circumstances, typically the litter will appear well but will start to "run off" at 7-10 days as the increased demand for milk is not met. A hardening and tapering of the udder tissue can be detected at the point of connection with the belly at 24 hours post farrowing. Hardening of the udder close to the teats will not occur until later and once detected it is likely that it is too late to 'save' the udder for that lactation. The sow may be reluctant to allow sucking by this stage.

Oedema (fluid build up) - often referred to by stockmen as udder congestion - will often be evident between the back legs and down into the posterior glands when congestion of this nature occurs.

As excessive milk is produced and not removed the pressure builds up in the udder with the result that damage is caused to the cells that produce the milk limiting further production. Moreover, as the cellular damage increases, endotoxins will be produced in the udder which can lead to pyrexia (high temperature) loss of appetite and general lethargy. The udder may become hot and painful as a true mastitis ensures, but this is very much an end point of the condition.

Overfeeding prior to farrowing - particularly with high protein lactator ration is the most common cause of this problem and a specific feeding regime must be tailored to each farm, taking into account feed used, genotype, housing provision and various managemental factors. Where this condition is recognised as a problem the immediate response must be to relieve the pressure in the udder. This can be done: -

a) By manually milking out the sow (if necessary aided by oxytocin injection); any colostrum collected in this way can be stored in a freezer for later use in weakling pigs.

b) Use of a human breast pump to achieve the same end.

c) Boxing the sow's own litter away and temporarily placing strong 10-14 day old pigs onto the sow (having prevented them from suckling their own mother for 2hours) for 1 hour to take the milk away. Care is needed not to transfer disease such as scour by this technique.

As a general rule feed levels need to be reduced in the immediate pre-farrowing period. A typical protocol would be:

1) At 12-13 weeks gestation increase feed level by up to 50% (using dry sow diet).

2) On entry to farrowing houses (15 weeks +) reduce to previous base level but using lactator ration.

3) 48 hours prior to farrowing reduce to 1kg/sow/day (measured), with the lack of dietary bulk made up with soaked bran.

4) Day of farrowing give bran only or very limited amounts of feed.

5) 24 hours after farrowing commence the steady building of feed on a daily basis with no pre-set maximum.

If problem still occurs consider delaying the change to lactator ration until after farrowing is complete.

Where the udder has partially or totally dried up, supplementary feed must be provided to the piglets (milk powder, electrolytes, creep feed), or they must be fostered onto a sow still yielding sufficient milk.

High concentrate feed intake pre-farrowing can also lead to bacterial endotoxin production in the gut, which can have an adverse effect on the muscle cells that trigger milk letdown with the same results and make the sow unwell. This is particularly a risk where pregnant sows are housed on straw based accommodation but move into farrowing houses with no roughage provided. The sudden reduction in dietary bulk fibre leads to gut stasis and increases endotoxin absorption from the intestine.

Mastitis

Apart from the secondary inflammation that can result from udder congestion, primary Mastitis can occur in two forms: -

a) Whole udder effect, Usually resulting from bacterial infection ascending teats and spreading through the udder via the lymphatic system, the condition is often acute (sudden in onset) and may be rapidly fatal. The udder will be hard, hot and painful. It is more common on systems using sawdust or wood shavings as bedding. Solid floor systems with poor hygiene are often implicated E.coli and Klebsiella are the most common agents involved. Appropriate antibiotic and anti-inflammatory treatments may save the sow but rapid action is needed for the piglets if they are not to starve. Where repeat cases are seen in a herd sampling the udder by milk draw or even needle biopsy is necessary to achieve a bacterial diagnosis and sensitivity indication.

b) Individual glands. Each individual paired gland can become infected and lose productivity. Actinomycosis of the udder in a specific condition which will destroy the gland completely and can cause abscessation and subsequent fibrosis. It is most commonly seen as the udder dries off after weaning. It most commonly affects the hind gland and then the loss of milk production capacity is limited to the poorer producing tissues.

Cost

The cost of a failure to milk properly can be measured in terms of the damage to the piglets (also allowing for early culling). Starvation and death can add a cost of £35-45/per pig to a breeder feeder farm (£30/per pig breeder weaner), as where the limit on growth of a litter from a sow in additionally milking would be more insidious. A loss of 1kg live weight/per pig a weaner is quite possible and would add 10 days to slaughter age at 100kg giving a cost just in extra feed supply of up to £4/per pig or £20 for an affected litter.

Thus a modest, even unrecognised problem in a 300 sow breeder feeder farm with half the sows affected would give an annual cost of £15-20,000, plus without additional mortality.