Introduction

Mixed respiratory disease is reported as one of the most common clinical conditions affecting growing pigs in the UK by NADIS reporting veterinary surgeons. As part of the collection of micro-organisms causing this syndrome, Actinobacillus pleuropneumonia can be an important contributor. It may also, however, exist as a stand alone uncomplicated condition either causing acute epizootic disease or chronic low grade infection. The organism has been recognised as causing major loss to UK producers since the late 1970's and remains an important pathogen.

Fig: 1: Chest wall of a pig suffering acute Acpp. Note roughened surface with pleurisy.

Fig 2: Acute haemorrhage in lungs of pig affected with Acpp.

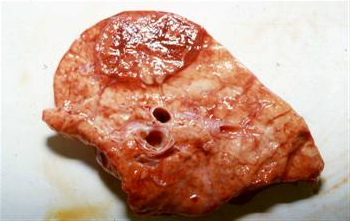

Fig 3: Typical 'core' lesion in lungs at slaughter from pig chronically infected with Acpp

Fig 4: Typical chronic pneumonia involving Acpp in growing pig.

The Cause

The cause of pleuropneumonia (previously known as "Haemophilus") is a bacteria called Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, of which there are many strains recognised worldwide and many subtypes within each strain. The ability of different strains and subtypes to cause disease varies widely and it is strongly suspected that a large proportion of farms are infected with mild or non-pathogenic subtypes without disease ever becoming evident. In the US, it is claimed that 80% of farms are infected but disease is only seen in 20%. The bacteria appears to be able to survive for long periods in the tonsils of normal pigs.

Whilst the acute clinical disease primarily affects the growing pig, in naïve situations adults and baby piglets (as young as 10 days old) can be affected.

The principle mode of spread of the disease onto a farm will be in infected normal pigs with local aerosol spread within the farm. The disease does not appear capable of spreading more than 600-800m from farm to farm on the wind but transmission over distances by contaminated fomites is possible.

Clinical Signs

In an acute outbreak of the disease, the early signs may be "sudden" death in large well fleshed growing pigs. There may well be blood tinged froth leaking from the nostrils.

Live pigs will be very depressed and reluctant to rise and exhibit difficulty breathing. There will often be only a low level of cough - which is a feature that helps differentiate the disease from Swine Influenza. Rectal temperatures can be very high - in excess of 42°C (107.5°F).At post mortem examination, the lungs will be solid and haemorrhagic and covered in a film of pleurisy that resembles buttered bread. The affected lung tissue can almost resemble the liver. There will be excess fluid in the chest and occasionally in the abdomen. Lymph nodes are enlarged and occasionally haemorrhagic.

In longer standing chronically infected invidivuals lung necrosis and abscessation may be seen and the lungs can become adhered to the chest wall as the pleurisy organises to fibrous tissue. The disease may affect whole buildings or just in pockets and can often be triggered by other respiratory insult (e.g. variable temperatures, high leves of aerial pollutants such as ammonia, Swine Influenza infection, Enzootic Pneumonia etc).

In a chronically infected farm, rather than seeing the dramatic picture described, the organism may become part of the soup of pneumonia organisms that caused long term low grade loses in the growing herd - often associated with PRRS (Blue Ear) and Mycoplasma infection. Alternatively, low-grade infection can occur on its own causing periodic or permanent losses The diagnosis is confirmed in the laboratory by culture of the organism.

Treatment

Whilst therapeutically the drug of choice for acute disease is Ceftiofur, this antibiotic is now of critical importance in the treatment of human infections and as such should only be considered as a last resort in the farm situation - where alternatives have failed and sensitivity tests from farm isolates supports its use. Alternative individual injection treatments include florfenicol and long acting macrolides such as tulathromycin. In an acute outbreak, pigs will neither eat or drink and, therefore, injection of individuals, often in large numbers, is the only option.

As the outbreak subsides, medication of the water or feed with appropriate antibiotics (e.g. Amoxycillin, tetracyclines or potentiated sulphonamides) can be effective.

In feed tilmicocin (Pulmotil (Elanco)) is a highly effective antibiotic against Acpp and can be used in treatment of acute disease, control of chronic outbreaks and even in specific cases on part of a programme to eliminate the organism. Details can be obtained from your own veterinary surgeon who can tailor a plan to suit individual circumstances.

In chronic complex cases, attention to environment and other organisms is necessary to reduce the overall challenge to the pig. Vaccination for Enzootic Pneumonia and/or PRRS can help control disease associate with Acpp by reducing primary lung damage and immune compromise.

Prevention

In the ideal world, the aim must be to keep this disease out of a herd. This is tempered by the difficulty in knowing whether the organism is present in a herd if it is not causing clinical disease.

Where it is known, attention to housing and management are essential with the following broad areas requiring attention:-

1) Thermal comfort

2) Fresh air provision

3) Stocking density and group size

4) Nutrition and water supply

5) Stockmanship including early disease recognition

6) Control of complicating disease including viral infections.

7) Hygiene

8) Pen management and flow (e.g. al in all out; age separation)

Where the organism is recognised as causing long term intractable problems, vaccination of the young pigs with a commercial vaccine may be appropriate. However, there is currently a licensed vaccine available against Acpp in the UK but in practice it is not always as effective as required.

As an alternative, it is possible, via the veterinary surgeon, to have a special (autogenous) vaccine made under DEFRA licence.

Typically, vaccine is given as 2 doses to growing pigs such that the second dose is given at least 2 weeks before expected disease. In some situations, vaccination of the breeding herd instead of or as well as the growing pigs is necessary.

In all cases it is not appropriate to rely long term on antibiotic medication to suppress disease.

Where control cannot be satisfactorily achieved or the cost of control measures is unacceptable, elimination programmes based on total or partial herd depopulation programmes is appropriate.

Costs

Complex respiratory disease can contribute 5% to herd mortality (especially where PMWS is involved) and can reduce growth rates by 100gm/day and depress feed conversion efficiency by up to 0.5. On a herd basis this can impose a cost in excess of £5/pig produced. Whilst controlling Acpp alone will not remove this, if it is a significant component of the disease then the cost of control must be evaluated in the light of these losses