Aspergillosis

Fig 1. Aspergillus. Cloudiness in air sacs

Cause:

Any disease caused by a member of the Aspergillus fungal family is identified as Aspergillosis. It causes three primary disease patterns which affect variously the respiratory tract, the eye and the brain. Fungal spores can often be found in wet, poorly stored straw. Bedding should always be carefully sourced.

Signs:

That seen in game birds most commonly is seen as pneumonia or sacculitis. (Figs 1 and 2) (As might be expected presenting signs are laboured breathing which in the terminal stages is gasping, with the beak open and neck stretched in an attempt to get sufficient air into the lungs. Also occasionally eye lesions occur (Fig 3).

Fig 2. Aspergillus. Advanced air sacculitis

Fig 3. Aspergillus associated kerato-conjunctivitis. Section through eye

Avian encephalomyelitis (Epidemic Tremors)

Cause:

Avian encephalomyelitis virus. A picorna virus.

Signs:

Although thankfully not too common in game birds in the UK, it does have devastating consequences if introduced to a flock. It is most often seen in very young birds. Presenting signs are a characteristic trembling (or tremor). (Fig 4) Affected birds are very obviously dull and depressed. The rate of infection (morbidity) is very high (40-60%) and rapidly spreads from group to group on the same unit (especially if there are varying age groups there, as is often the case). Mortality may be as high as 50%.

Fig 4. Avian encephalomyelitis. Trembling makes sharp focus impossible

Spread:

Infection can be egg transmitted and so the disease can unknowingly be bought-in with chicks. Virus is shed in high quantity in the droppings and may remain infective for a long time.

Action:

Because of the highly infectious nature slaughter of affected birds may be considered as a control measure. Vaccine is available for breeder flocks.

Chilling:

When, for any reason, the heat source fails in young birds they will huddle and eventually heap to try to get warm. This usually leads to death by smothering (see Smothering below).

Colibacillosis/coli septicaemia

Cause:

Colibacillosis is usually caused by Escherichia coli but can also be caused by other coliform bacteria. There are many strains of E. coli normally living in the intestinal contents without causing any trouble. Under certain conditions however, especially when the bird is stressed or suffering from another illness, particular strains may spread to other organs causing disease and eventually killing the bird.

Birds may be affected at any age, but it is mainly seen in (very) young or immuno-suppressed birds.

Spread:

The infection is not contagious. Birds can only pick it up from the environment.

Colibacillosis is found world wide and can occur anywhere and any time birds are living in damp dirty litter. Day olds can get infected in the hatchery when eggs are contaminated with droppings in the laying pens.

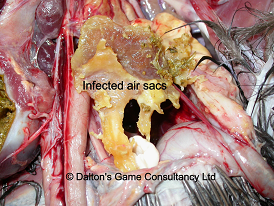

Signs:

Septicaemia, or blood poisoning, is the most common acute form. (Fig 5) Later losses are usually due to pericarditis or perihepatitis, a white covering around the heart or liver. The liver is black and smelly and the spleen enlarged. A blood smear, including those taken from bone marrow, will show several rod shaped bacteria.

E. coli is often found as a secondary pathogen with other conditions such as coccidiosis, mycoplasmosis or Histomonas. The damage caused by the primary pathogens make possible the colonisation by E. coli strains that normally would not be able to cause any problems. The secondary damage done by E. coli will often result in death.

Fig 5. Colisepticaemia. Haemorrhages on surface of intestines. Congested blood vessels in major organs

Treatment:

Treatment consists of antibiotic therapy. Preferably the organism is isolated, typed and a sensitivity test carried out to determine the right antibiotic.

Control:

Antibiotic treatment can not cover up bad hygiene! Sanitation of the environment, drinkers and feeders is more important. Restrict the contact of birds with droppings. To prevent problems occurring thoroughly clean and disinfect brooder houses in between hatches. Keep litter, feeders and drinkers as clean as possible. Dead birds or unhatched eggs should be removed and incinerated as soon as possible, unless they are going to be brought in for post mortem.

Don't forget cleanliness in egg gathering, cleaning, storing, incubating and hatching.

Mycoplasmosis (Bulgy eye)

Cause:

Mycoplasmosis has been recognised in pheasants and partridges since the 1950`s. The commonest organism found in our species is Mycoplasma gallisepticum. There is a whole host of related bacteria, but their ability to cause disease is not always known.

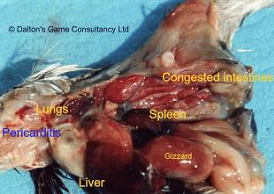

Signs:

Clinical disease is most often seen in adult birds although all ages may be affected. Mortality in chicks 7 to 14 days old can be devastating.

Respiratory symptoms and sinusitis ("bulgy eye"). Joint infections may be seen as well (see below). Clinical signs develop slowly within the flock but stress, poor ventilation, and a cold and damp environment will make things worse. Signs include ocular discharge, swollen sinuses, (Fig 6) sneezing, mouth breathing and a reduced growth rate. Egg production is also affected with reduced production and hatchability and pale coloured eggs with thin shells. Joint infections are seen mainly in the leg joints (mainly the hocks). These are swollen and the joint space often contains orange coloured liquid, with the lining of the space thickened (synovitis). It is thought that Mycoplasma synoviae is involved in this, but this has yet to be proved.

Fig 6. Bulgy Eye. These chicks are showing typical swelling below the eye

Spread:

Bird to bird close contact, via air droplets, infected litter and equipment (horizontal transmission), and from hen to chick via the egg (vertical transmission). Recovered birds will remain carriers and shedders; therefore, once your flock is infected it will remain infected.

Treatment:

Treatment of clinically diseased animals should only be carried out to salvage the shoot of that year. Do not keep any recovered animals for breeding, as they will most likely be carriers! The bacteria are sensitive to several antibiotics and are easily destroyed by sanitisers, disinfectants and direct sunlight. Control will mainly be aimed at breeders. When catching up birds, cull animals that show any signs of disease. When Mycoplasma is present on the shoot it is possible to treat the birds with antibiotics during stressful periods, please discuss this with your vet.

Control:

Try to keep a closed flock, but when you have to buy-in try to buy birds from reputable sources. Bought-in birds must be quarantined before being added to the resident flock. Never forget the importance of good management (especially drinkers) and biosecurity!!

Vaccine:

There is a live commercial poultry vaccine available for spray vaccination in poultry in the UK. It may give some protection in gamebirds. Care must be taken when giving these vaccines. It is vital to follow the instructions closely!

In mainland Europe there is a killed injectable vaccine that has been used in the UK as well. Once again it is not clear how much the protection is given to gamebirds when it is used. There are also risks to anyone using the vaccine if they accidentally self-inject.

Navel ill

See under Yolk sac infection

Newcastle disease

Significance:

Although you should not see this in birds of this age, it has to be described here because of the potential severe consequences, both in mortality because of the disease, and possible compulsory slaughter of affected flocks if it is confirmed.

Cause:

Newcastle disease is a notifiable disease caused by a Paramyxovirus Type 1. It is spread worldwide and can cause considerable losses. Over 250 bird species are susceptible!

The virus was first isolated in 1926 in the Far East, thereafter it was found in Newcastle upon Tyne (hence the name).

Signs:

The disease was first reported in pheasants in the UK in 1963. The severity of the disease depends on the virus strain, the species affected, the immune status, condition and age of the bird and whether the birds are suffering from concurrent diseases.

The respiratory system, the intestinal system and the neurological system can be affected.

Symptoms include respiratory disease, diarrhoea, nervous signs, swelling of the neck and face and sudden death. Hens may stop laying or produce misshapen eggs. In severe outbreaks mortality can reach 90%! In young birds, nervous signs with sudden high mortality are most likely to be seen.

Post mortem:

There are no specific diagnostic lesions. There may be haemorrhages in the intestinal mucosa, cloaca, pancreas and proventriculus. There can also be congestion in the lungs, liver, spleen, kidney and air sacs. The liver may be discoloured and there may be an enteritis and weight loss.

Diagnosis:

By blood samples or virus isolation from the cloaca, trachea or brain.

Spread:

Can be spread by direct contact with excretions, especially droppings, from infected birds. Infection may occur orally or by inhalation.

The disease can be spread by any one of the following:

Movement of live birds

Airborne spread

Contaminated feed or water

Non avian animals

Vaccines

Movement of poultry products

Movement of people, vehicles and equipment.

Newcastle Disease is notifiable but statutory action only needs to be taken for virulent strains. The last virulent outbreak in England was in 2005 (in pheasants imported from France).

In case of an outbreak, there will be a ban on the export of live birds, eggs and poultry products. The length of the ban and the effect on the poultry and allied industry will depend on the extent of the spread and the time taken to eradicate it.

Treatment/Control:

There is no treatment for the disease. Control will depend on good biosecurity measures combined with vaccination and / or eradication. In most countries eradication by slaughter has become the main policy, however, one needs to consider the economical and political pressures in most European countries.

Vaccination will prevent deaths, clinical signs and egg production problems but will not prevent birds getting infected. Infected vaccinated birds will still excrete the virus but in relatively small amounts. Therefore many countries will not accept vaccinated birds.

Ricketts

Cause:

Calcium or Vitamin D deficiency. Generally seen in birds slightly older than 10 days, but in severe cases may be younger.

Signs:

Birds usually present with lameness and ability to walk or stand. Limbs may be bent.

It is because is usually dietary that it is seen at 2 to 4 weeks old. If the egg itself is very thin shelled, resorption of calcium from the shell to the chick in late stage incubation is poor and they may theoretically be born affected.

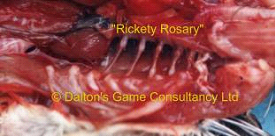

Fig 7. Rickets in young pheasant. "Rickety Rosary". Internal

Post mortem signs:

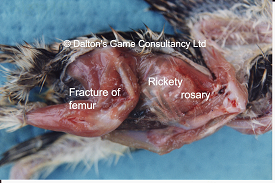

There is often swelling along the line of the junction of the bony section of the rib with the cartilage, leading to what is classically described as a "Rickety Rosary". (Fig 7) As you run your fingers along the line there is a distinct knobbly feeling. The long bones of the leg may be bent, rubbery or even have spontaneous fractures. (Fig 8).

Fig 8. Rickets in young pheasants. Fracture of femur and "Rickety Rosary". External

Rotavirus enteritis

Cause:

Rotavirus. Is seen more and more frequently. It affects poults from a few days old, right up to 7 or 8 weeks (or more) of age.

Signs:

Vary with the age of the bird affected. In the first week of life moist droppings, lethargy and sometimes a string of sticky droppings trailing behind the bird may be seen. Mortality is variable, but can be as high as 80%! A high proportion may look pretty poorly. Sometimes you may find a heap of dead birds first thing in the morning. There is often a characteristic smell in the house or shed, associated with the very liquid droppings. Food consumption usually plummets, but birds will drink. You may find dead birds lying in the drinkers. The bedding material is wet in more places than just around the drinkers or feeders. 2 to 3 week old birds suffer lower mortality, but fail to thrive. They are often wet around the vent, huddling and eating less.

Once again large numbers can be affected. In the 5-week plus bird the signs are often complicated by the presence of one of other conditions such as Hexamita (Spironucleus), Trichomonas, Blastocystis and Coccidiosis, or a mixture of any of these. The droppings are characteristically pale to mustard yellow. Mortality in this age is low, but many affected birds never truly recover, going on to become the razor keeled rejects so often seen.

Diagnosis:

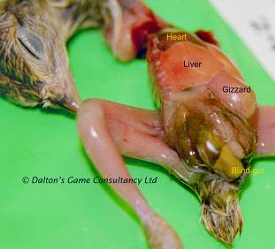

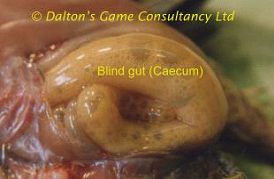

Is based on post mortem examination of affected dying birds and some already dead. Post mortem changes are usually seen in the blind gut (caecum), which is distended and contains yellow frothy or slightly pasty liquid. (Figs 9 a & b) It is not possible to differentiate between these gross signs and those of acute early coccidiosis without microscopic examination of the gut contents. CORRECT AND ACCURATE DIAGNOSIS IS VITAL. Ultimate diagnosis depends on identification of the virus by electron microscopy. This is a disease most commonly associated with poor egg hygiene, incubator technique and hatchery management. Infection is also transmitted from the hen through the egg to the chick.

Figs 9a (above) &9b (below). Rotavirus infection. Distension of blind gut (caecum) with frothy yellow liquid

Treatment:

There are no specific medicines available that act directly on the virus. Treatment of affected birds relies on: Electrolytes, antibiotic cover, vitamins, extra heat, disinfection and protection of other birds. Medicated water must be supplied fresh at least twice per day. Drinkers must be disinfected at least once a day. Wet patches and popholes should be treated with disinfectants or desiccants. Boots must be disinfected before and after seeing to the birds. Separate overalls should be worn in affected houses. Dead birds and contaminated bedding and chick boxes must be burnt. This is a highly infectious disease; spread by humans is as common as by birds.

Salmonella enteritis

Figs 10a (above) &10b(below). Salmonella. Pheasant Caeca with hard cores

Cause:

Various members of the Salmonella group of bacteria.

Although this can cause serious disease in young birds, often with high mortality, it is also a Zoonosis and must be reported to Defra if it is diagnosed.

Signs:

As with so many diseases of very young birds often all you see is "sickly" looking birds.

Post-mortem signs:

Sometimes "classical" white cores are seen in the caeca. (Figs 10 a & b) However, such cores can also be seen in coccidiosis, so absolute diagnosis in the laboratory is essential, not only to get the correct treatment, but to make sure that the Public Health risk is minimized.

Smothering

Although not an infectious disease this is a common cause of mortality in young poults. There are basically two causes. One is huddling because of chilling when the background temperature is too low. The other is when birds are panicked into a heap. This can happen when there are storms or predators get into or near the brooder hut or grass run.(Fig 11)

Fig 11. Smothering. Close up of heart. Often elongated, or slightly "pointed" in smothered birds.

Starve-out

Cause:

Although regarded as many as "normal", starve-out is in fact a "disease" which is triggered by the artificial rearing of chicks. The broody hen encourages her young to eat by demonstrating scratching and turning up food for them. In the brooder hut, although the food is likely to be plentiful, the young chick may fail to eat and hence "starve out" for a number of reasons. These include being too hot, too cold, too crowded, dehydration, poor access to feeders, unpalatable feed (maybe when it has been over-heated, stale or incorrectly stored) as well as suffering from other diseases.

Signs:

The chick will survive for several days without eating; relying of the nutrients remaining in the yolk sac to keep it going. As the yolk sac is resorbed the food value drops and unless replaced by true food, the chick's blood glucose level falls. This in turn leads to reduced activity and appetite, setting it only the downward spiral to death. "Starve-out" peaks at 3 to 4 days old. If mortality continues beyond this time, an urgent investigation into other causes must be made.

Chicks that have died of starvation typically have an empty crop and gizzard and a distended gall-bladder. (Fig 12).

Fig 12. Starve-out. Distended gall bladder

Fig 13. Yolk sac infection.

Yolk sac infection / Navel ill

Cause:

Bacterial infection either of the navel either during incubation or soon after hatching. As the chick develops in the egg, the yolk lies outside the body cavity, connected to the intestines of the bird by the umbilical cord. The embryo will use about 80% of the yolk sac contents during incubation. The remainder of the yolk sac gets withdrawn into the body cavity 2 to 3 days before hatching. The rest of the yolk will be used up in the first 5 days of life by which time the chick should be able to eat and drink the provided water and food. The yolk sac does not only provide an excellent source of food for the embryo. It is also very attractive for invading bacteria such as E. coli, Staphylococcus, Bacillus cereus, Enterococcus, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Clostridium and Proteus. Infection is contracted from the environment and is not usually spread from bird to bird, but infected birds may contaminate others around the time of hatching.

Birds can get infected before eggs are set, during incubation or during transport or early brooding.

The egg shell is full of pores, but is protected by a cuticle. When this cuticle is damaged or removed bacteria can penetrate the egg through the pores. Active scrubbing of eggs to clean them will do just this. Bacteria can also penetrate if the eggs are laid in a dirty environment, especially when left for a while, as bacteria will be drawn in to the egg as it cools down. If eggs are washed in a cold solution this process is accelerated.

During incubation dirty eggs or contaminated air are responsible for infection. Too high or too low humidity will increase problems. If the hatching is slowed down and the navel is slow to heal there is a greater chance of bacteria invading via the navel. Handling eggs / chicks with contaminated hands also increases the infection rate.

Signs:

Chicks may be healthy when leaving the hatchery, but infection can enter via the intestines if the birds are stressed during transport or early brooding, also chicks can get infected via unhealed navels. When birds get infected early in life the embryo may die in the shell or shortly after hatching. With later infections birds usually start off normally but will become depressed and die a few days later. A large yolk sac will be found with very fluid yolk. (Fig 13) Often there is peritonitis with a very rotten smell. The chicks die from the toxins produced by the bacteria or from septicaemia. Yolk sac infections are always caused by bacteria. Isolation and identification is needed to determine the source of infection and probability of an ongoing problem.

Treatment:

There is no treatment as most chicks will die within the first few days. One can only give supportive therapy such as electrolytes and vitamins.

Action:

When mortality exceeds 3% an investigation should be carried out into egg shell quality, egg handling and sanitation. Incubation / hatching procedures, machine sanitation and other possible contributing factors such as ventilation, personnel etc.