Pheasants (Phasianus colchicus), Red Legged (French) Partridge (Alectrois rufa) and Grey (English) Partridge (Perdix perdix)

The More Common Diseases Seen In Game Bird Laying Flocks

Many of the problems seen in the laying flock are a consequence of poor breeding stock selection. If you have seen a significant number of birds showing respiratory signs, such as Bulgy Eye or coughing during the shooting season it is vital to get a 100% diagnosis before considering your own caught-up stock as laying birds. Some of the problems seen in adult birds can also show in younger stock.

Ascarid worms

These parasites are unlikely to cause serious trouble in adult birds. Controlled by routine worming.

Avian Influenza

A Notifiable disease often causing very sudden, high mortality. Some variants can cause significant disease in humans.

Clinical signs:

Depend largely on whether the virus causing the disease is Highly Pathogenic (HPAI) or Low-Pathogenic (LPAI). In HPAI sudden onset high mortality is often the first sign seen. Decreased egg production, soft-shelled or misshaped eggs, swelling of the head, eyelids, comb and wattles, sometimes with purple discolouration of the wattles, comb and legs, respiratory signs such as coughing an sneezing, and loss of co-ordination have all been reported. In LPAI signs may be of a simple malaise, with affected birds slightly "off colour". Images of affected poultry can be viewed at

http://www.defra.gov.uk/animalh/diseases/notifiable/ai/factsheet/photo.htm

If you have any suspicion of avian influenza in your birds you must, by law, report it to Defra.

Post mortem findings:

There are few records of clinical signs in gamebirds. It might be expected that they would be similar to those seen in chickens and turkeys. Post mortem signs are many and varied. Some are sinusitis, tracheal inflammation, air sacculitis, egg peritonitis, necrosis of liver and kidney and a wide range of changes from seep red to almost purple/blue in the comb and wattles. Secondary bacterial infection may confuse the signs as well.

Diagnosis:

Virus isolation from swabs from the vent and detection of antibodies by serology. Antibodies may be seen just over a week after infection.

Spread:

Virus is swallowed in contaminated droppings. Virus is excreted in massive amounts in droppings.

Treatment and control:

As with most viral infections there is no specific treatment. A slaughter policy for affected birds or birds suspected of being infected in the United Kingdom and many other countries.

Prevention:

All plans throughout the world are centred on avoiding exposure to the virus. Good bio-security is vital. Isolation of any newly purchased stock before contact with resident stock is vital. Because of the high number of virus strains and variants vaccination is not feasible.

Avian tuberculosis

Virtually impossible to treat once well established. If found in a flock intense culling of affected birds and antibiotic treatment of remainder can help.

Blackhead

Primarily a parasitic disease (Histomonas) usually complicated by bacteria infection. Sudden death. Closely linked with Heterakis worms. NB Turkeys are particularly susceptible.

Bulgy Eye (Mycoplasmosis)

Fig 1: Mycoplasmosis: Swelling of the tissues around the eyes and nasal discharge is usually seen

Fig 2: Mycoplasmosis: The sinuses under the eyes are often filled with pus

This is a bacterial commonly caused by Mycoplasma gallisepticum.

Clinical signs:

Birds have swelling around the eyes, usually below the eye. This can be so severe that the eyes are closed, making the bird blind. There is often a discharge from the eyes and external nares of the beak. Birds usually sneeze, cough and regularly shake their head.

Post mortem findings:

The sinuses below the eyes are commonly filled with either very sticky pus, or may even have solid lumps of pus forming a perfect cast of the sinus. Cloudiness in the air sacs and even consolidation of the lungs may be seen.

Diagnosis:

Specialist swabs need tobe taken by a vet or alternatively fresh samples can be sent away for analysis. It is also possible to check the antibody levels of suspected birds by blood testing.

Spread:

Between adults this is by droplet infection from bacteria sneezed or coughed out by other birds, from drinking contaminated water or eating contaminated food. It can be harboured in the bird, showing no clinical signs until it is placed under stress in some form e.g. moving,coming into lay or suffering other disease.

Treatment and control:

There are commerical and autogenous vaccines available in the UK, these vaccines can be injected intramscularly or sprayed. Theses should be considered as one of the steps in avoiding the problem. Less severe cases will respond to antibiotics in water followed by in-feed medication.

Fig 3: Mycoplasmosis:: Infected thoracic air-sac

Very severe cases should be culled, as it is virtually impossible to cure those with solid pus in the sinuses. If you suspect that caught-up (or bought-in) laying stock have either been exposed to infection or may be carrying it routine medication should be carried out to prevent an upsurge when they come into lay. Don't forget that all the antibiotics available must be prescribed by or purchased from a vet.

Other factors:

This can be transmitted to eggs through the ovary. Infection in young chicks can lead to high mortality

Fig 4: Mycoplasmosis: Contaminated drinkers are involved in the spread of disease

Capillaria. (Threadworm)

Heavy infestation can cause ill-thrift in older birds. May kill younger birds. Diagnosis by finding of easily recognised eggs in intestinal contents and particularly wet-slide scrapes from the mucosa of the crop.

Corona-nephrosis. (Whitchurch disease)

A viral infection caused by infection with a member of the Infectious Bronchitis group.

Fig 5: Corona-nephrosis: Dramatically enlarged kidneys

Clinical signs:

Most commonly the first indication in the laying flock is sudden mortality in what look like otherwise healthy birds. The onset of the disease is so rapid that there is seldom time for significant weight loss. Those keeping good records of egg production will notice a rapid drop in eggs laid in the few days before the mortality starts. Food intake also drops in line with the egg production loss. Mortality can be as high as 50% of the flock.

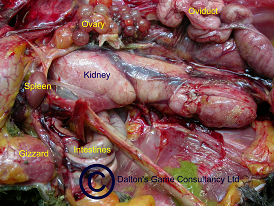

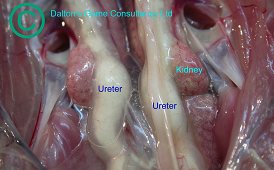

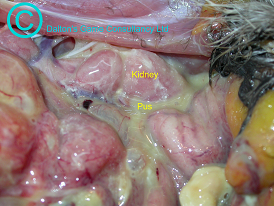

Post mortem findings:

The abdominal cavity is often filled with custard-like pus. There are often flocculent white lumps floating in this. The kidneys are usually dramatically enlarged, with a very pale appearance. There are often dark wavy lines crossing the surface of the kidneys. The heart and liver frequently have an uneven white covering (visceral gout) caused by deposition of urates which are usually excreted by the kidneys. The ureters are often distended with urates.

Fig.6: Corona-nephrosis: Grossly distended ureters.

Diagnosis:

The post-mortem findings are such that a very justifiable diagnosis of corona-nephrosis can be made on those alone. Viral particles can be isolated from material within the kidneys and histology ties up a firm diagnosis.

Spread:

As the name of the causal virus suggests, this is spread primarily by the respiratory tract. Recovered birds and those from an infected flock should not be released for several months as they will continue to shed virus for all that time.

Treatment and prevention:

There are no drugs available for use in poultry that specifically treat the viral infection. As with all diseases affecting the kidneys free access to good quality water is vital. The addition of electrolytes may be of benefit. There is some suggestion that mortality is reduced if the affected flock is treated with water soluble tetracyclines. There are many different Infectious Bronchitis vaccines available for use on the poultry industry. There may be some benefit to pheasants in using some of these. Individual vaccination by eye or nasal drops does appear to give better results.

Fig 7: Corona-nephrosis: Visceral gout on heart and liver

Fig 8. Corona-nephrosis: Custard-like pus free in abdomen

Gapes

Parasite (Syngamus trachea) latches on to the lining of the windpipe, causing characteristic "snicking". Worm eggs very persistent. Routine worming essential for control. Heavy infestation in young birds can kill.

Heterakis worms

Seen in large numbers in the lower intestine and blind gut. Cause ill-thrift, death in young birds and closely linked to Blackhead. Routine worming is essential.

Marble Spleen Disease

A viral disease which is usually associated with very sudden death, but not usually high numbers. Birds can literally drop dead off their perches. There is a vaccine available in mainland Europe, but is not used in the UK.

Newcastle Disease (Fowl Pest)

Another notifiable disease. A viral disease that can affect a wide range of birds (more than 250 species).

Clinical signs:

Various signs seen including nervous, signs (imbalance), respiratory disease, loose droppings, swelling of the neck and face and sudden death. Laying birds may stop laying or produce misshapen eggs. Mortality can be a high as 90%.

Diagnosis:

No specific lesions. Absolute diagnosis by blood sampling or virus isolation.

Spread:

Airborne, water, feed, movement of birds and people, equipment and vehicles.

Treatment:

None. Slaughter policy in place in UK.

Prevention:

Keep it out of the country! Vaccination reduces mortality and signs, but vaccinated birds can still be infected and continue to shed virus.

Spirochaetosis (Borreliosis)

Causes weakness, lameness and death. Spread by tick bites. Same ticks can bite and infect man. The pheasant is regarded by some as significant reservoir of infection.

Staphylococcosis

Bacterial infection that leads to lameness and multiple abscessation. Enters through damaged skin e.g. rough handling, damaged feet or specks and bits.

Turkey Rhino Tracheitis (TRT/Avian Pneumo-Virus)

Fig 9: TRT: Pheasant peri-orbital swelling

TRT is a highly contagious viral respiratory disease first found in turkeys (hence the name).

Clinical signs:

Most frequently encountered in birds at wood in late October/early November, but can also affect birds in the laying flock in large numbers. There appear to be two differing presentations. In the laying flock there is most commonly swelling around the head, above AND below the eyes. At wood it is most encountered as a dry, snicking cough, often audible from 150-200 yards from the birds.

The virus primarily affects the upper respiratory tract. It attacks the small hair like structures, called cilia, that line the inside of the nose and trachea (windpipe). These cilia catch any pathogens or dust particles that may have gained access to the respiratory tract and transport them back up. Infection with TRT stops these cilia beating, therefore allowing more virus, or other pathogens, to penetrate and damage the lining of the respiratory tract thus causing disease. As TRT makes it easier for other pathogens to cause disease it is often seen as part of a disease complex involving other pathogens such as Mycoplasma and E. coli. When complicated by these pathogens the lungs may be affected as well.

Fig 10: TRT: Same bird as Fig 9, 3 weeks later

Severity depends on age and species of birds, as well as the involvement of other pathogens. Uncomplicated cases will last from 7 to 14 days. Mortality is generally low. There is depression, snicking and coughing. The sinuses may be swollen, there may be a discharge from the eyes and excess mucus in the nostrils. It can cause a reduction in egg production and hatchability and can cause egg deformations. Growth rates will be reduced. A specific form is "Swollen Head Syndrome". In this case a severe secondary bacterial infection has penetrated the spongy bones of the head, often involving the middle ear which is associated with balance. The birds will have swollen puffy heads and may show head-rolling, stargazing and twisted necks. In this case mortality will be high as the birds cannot feed. As TRT facilitates other infections as well it may be possible that by vaccinating for TRT, the incidence of other respiratory may be reduced. Work has been published to show that successful vaccination with commercial poultry TRT vaccine is relatively simple in the rearing field. Spray or eye drop vaccination is vital.