Avian Influenza (commonly known as 'bird flu') is a highly contagious viral disease affecting the respiratory, digestive and/or nervous system of many species of bird.

There are many strains of Avian Influenza. Some of these strains are less harmful ('low path') whilst others are more harmful ('high path'). Some strains have the ability to infect more than one species; however the virus tends to have a preference for infecting one species, e.g. a strain of influenza that infects birds may readily spread between poultry or game birds but may struggle to infect people and will only do so in rare circumstances. Why human health professionals become concerned about bird flu is that if there ever was a strain that could infect both people and birds, it would be a challenge to control. Mortality in birds can be up to 100% and there is no treatment.

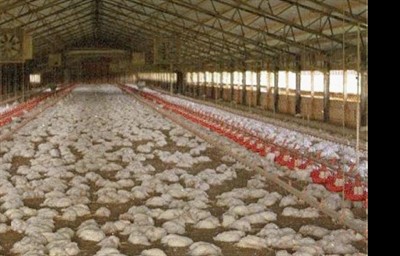

Fig 1 Mass mortality due to Avian Influenza in broiler chickens

The virus is often carried and spread by waterfowl that are remarkably resistant to disease and rarely show clinical signs. Because waterfowl often migrate large distances globally, Avian Influenza can move between countries readily. Furthermore, both people and contaminated objects can carry the virus long distances. Affected birds shed the virus in their faeces and via nasal discharge.

When Avian Influenza is suspected you must contact the APHA immediately either directly or via your veterinary surgeon.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs of Avian Influenza can be seen as soon as 24 hours after initial infection (usually in cases of a 'high path' strain). Sudden death is the most dramatic effect of Avian Influenza, oedema (swelling) of the head, cyanosis (blue discolouration) of the comb and wattles can also be seen. Dullness, a loss of appetite, depression, coughing, nasal and ocular discharge, swelling of the face, nervous signs such as paralysis and sometimes green diarrhoea are all also clinical signs. However, birds infected with 'low path' Avian Influenza may not show any signs at all.

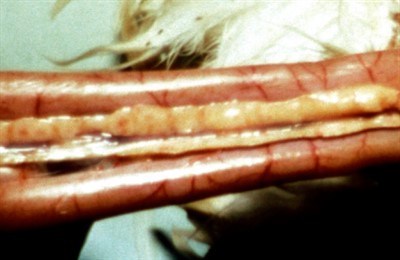

Fig 2 Chicken head cyanosis of comb and wattles

Post Mortem Findings

A post mortem of a bird with Avian Influenza may show inflammation of the sinuses, trachea and air sacs. Oedema of the head and discolouration of the skin may also be seen. Birds will likely show signs of dehydration and their muscles may be congested. Haemorrhages on the lining of the proventriculus, the glandular stomach, can also occur.

Fig 3

Fig 4

Figs 3 and 4 Subcutaneous haemorrhages

Fig 5 Haemorrhage into the pancreas

Diagnosis

A presumptive diagnosis can be made based on history, clinical signs and post mortem findings, but a conclusive diagnosis is made via testing authorised by the APHA.

Treatment and Control

There is no readily available treatment for Avian Influenza and most countries have a culling policy of affected birds. It is possible to produce a vaccine, but by the time this becomes commercially available the virus is likely to have mutated. Also, vaccinations can lead to 'masked infections' where the bird has the virus but is showing no signs, and can therefore pass it on to other birds.

A crucial part of the prevention of Avian Influenza in your flock involves keeping wild birds away. Keepers of waterfowl should especially try to discourage wild birds from swimming in their ponds. The virus survives very well in ponds and lakes. If there was an outbreak, birds should be kept in their overnight accommodation 24/7, so make sure it is of sufficient standard were this to be the case.

Biosecurity

Biosecurity is paramount to preventing Avian Influenza. A lack of a good biosecurity plan will lead to a heightened risk of disease transfer. To maintain strong biosecurity it is important to clean equipment regularly. This includes houses, pens, drinkers, feeders, quad bikes and trucks. The 3-D's are an effective code to live by. First, drench, power wash everything to remove organic material, then allow to dry completely. Next, detergent, use a powerful cleaner and degreaser, then again allow to dry completely. Finally, disinfectant, spray a disinfectant known to kill Cocci and viruses. Water systems need to be cleaned thoroughly, a hydrogen peroxide based clean will remove organic biofilm and algae.

To help reduce the spread of disease across pens have foot dips available for all transitions between different areas, the foot dips need to be covered and regularly changed.

Key Bio-Security Procedures

Fig 6 Drench, power wash everything to remove organic material.

Fig 7 Allow to dry completely.

Fig 8 Use a powerful cleaner and degreaser, then again allow to dry completely.

Fig 9 Finally disinfectant. Spray a disinfectant known to kill Cocci and viruses.

Fig 10 Water systems need to be cleaned thoroughly, a hydrogen peroxide based clean will remove organic biofilm and algae.

In summary, good husbandry is one of the best ways to prevent Avian Influenza. You should inspect your birds daily, and review your current biosecurity procedures and amend if necessary. Clean and disinfect all equipment, clothes and footwear before and after use, and provide separate clothing and footwear for different premises. Remember - whilst Avian Influenza is easily spread, it is not resistant to disinfectants or soap.