Fasciolosis is a common parasitic disease of both cattle and sheep in the UK, caused by Fasciola hepatica and is estimated to cost the cattle industry £23 million annually.

In cattle, infection is more commonly encountered in beef cows grazing poor wet pasture but disease can be seen in dairy cattle especially after summering cattle, most likely bulling heifers, away from home on infested pastures.

Life cycle

The life cycle involves a snail host whose activity and availability require adequate moisture and a suitable ambient temperature during the summer months. Recent wet summers (2015) have been ideal for this complicated fluke lifecycle by supporting large numbers of snails in wet habitats. Cerceriae are released from snails between August and October which develop- into the infective metacercariae, which can survive on pasture for several months to infect grazing cattle. Disease is then seen in cattle from mid-winter onwards (except for Black disease - see below).

Fig 1: Lifecycle of F. hepatica

Fig 2: Typical high risk fluke pastures are often grazed by beef cows and growing dairy heifers.

After ingestion by the host, the metacercariae develop within the small intestine and penetrate into the peritoneal cavity, going on to invade the liver capsule reaching the bile duct after six to eight weeks. Egg-laying adults will have developed 10-12 weeks after ingestion. Infected cattle produce an intense fibrous reaction within the liver, with the resultant fibrosis much more severe than that observed in sheep.

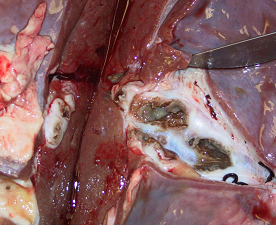

Fig 3: Surface of a fluke infested liver (see cut section in Fig 4) with massive enlargement of hepatic lymph nodes and white tracts visible on the liver surface.

Fig 4: Marked fibrous reaction (white areas) surrounding the bile ducts in this fluke-infested liver.

Clinical signs

Dairy cows

In severe chronic infestations, dairy cows show reduced milk yields and poor fertility together with excessive weight loss. Many show chronic diarrhoea.

Fig 5: In severe chronic infestations, dairy cows give a reduced milk yield and have poor fertility.

Fig 6: In severe chronic infestations, dairy cows lose excessive weight and have chronic diarrhoea.

Beef cows

The clinical signs are similar to those encountered in dairy cows but can be especially severe in spring-calving beef cows where liver fluke exacerbates the metabolic demands of advanced pregnancy in cattle on marginal winter rations. This results in the birth of weakly calves to cows with little milk, causing high perinatal losses. Severely affected cows may become debilitated with an increased incidence of metabolic and infectious diseases at calving.

Fig 7: Emaciated spring-calving beef cow with chronic fluke.

Twin-bearing cows show the most severe signs due to the high demands of two foetuses. Unlike infestation in sheep, peripheral oedema is a less common finding with chronic fasciolosis in cattle. Severe infections may cause anaemia.

Bulls

Infested bulls show similar clinical signs as cows such as chronic weight loss and diarrhoea.

Fig 8: Diarrhoea and early weight loss in a Limousin bull with liver fluke.

Fattening cattle

UK slaughter plants are reporting increasing numbers of liver condemnations due to fluke damage in 12 to 18 month-old fattening cattle where reduced liveweight gains were not suspected by producers presumably due to low-moderate infestation levels.

Fig 9: UK slaughter plants are reporting to farmers increasing numbers of liver condemnations due to fluke damage in fattening cattle. (Note the mud to the knees on these cattle grazing wet areas)

Differential Diagnoses

Weight loss and chronic diarrhoea in individual cattle will also be investigated by your veterinary surgeon for paratuberculosis and salmonellosis. Chronic liver fluke and paratuberculosis have been reported in the same animal. Other causes of chronic weight loss in adult beef cows could include other bacterial causes such as pyelonephritis, vegetative endocarditis, chronic mastitis, and chronic suppurative pneumonia.

Fig 10: Weight loss and chronic diarrhoea in individual cattle will be investigated by your veterinary surgeon.

Fig 11: Your veterinary surgeon may check for paratuberculosis and salmonellosis as well as chronic fluke.

Fig 12: Chronic weight loss in adult beef cows could be caused by other diseases such as pyelonephritis.

Fig 13: Your veterinary surgeon may also check for other causes such as vegetative endocarditis, chronic mastitis, and chronic suppurative pneumonia.

Inadequate nutrition generally presents as a whole group/herd problem of poor production and weight loss during the late winter months in beef herds with diarrhoea an uncommon finding unless poor quality silage is fed.

Chronic fasciolosis is diagnosed by demonstration of fluke eggs in faecal samples. Although fewer eggs are seen than in sheep, recent investigations have reported higher counts than generally expected from cattle. The sensitivity of egg counts in heavy fluke infestations is around 50 per cent so several samples from your herd will be examined by your veterinary surgeon.

There is a specific liver fluke blood and milk test with sensitivity and specificity values above 90 per cent but this test is expensive and may indicate prior exposure as well as active infection.

Treatment

Triclabendazole is effective at killing all stages of triclabendazole-susceptible flukes from two weeks old. Cattle may be slaughtered for human consumption only after 56 days from last treatment. Do not administer to cows producing milk for human consumption. Intensive use or misuse of preparations such as triclabendazole can give rise to drug resistance with reduced efficacy of the preparation.

Nitroxynil is licensed for the treatment of fascioliasis (infestation of mature and immature Fasciola hepatica more than 8 weeks after infection). The interval between nitroxynil treatments must not be less than 60 days. Cattle may be slaughtered for human consumption only after 60 days from last treatment. Do not use in cattle producing milk for human consumption.

Clorsulon is only effective against adult flukes. Cattle may be slaughtered for human consumption only after 60 days from last treatment. Do not administer to cows producing milk for human consumption nor dairy cattle including heifers within 60 days of calving.

The recovery of chronically infected cattle is slow following treatment with a flukicide. Improved nutrition of affected cattle is essential to restore body condition and production. Treated cattle should be moved to clean pastures wherever possible.

All withhold times etc. can change so always check the data sheets for the latest information.

Prevention/control measures

- In areas with endemic fasciolosis, control is founded upon strategic flukicide treatments outlined in the veterinary herd health plan.

- Where cattle are in-wintered a single dose of a flukicide, effective against appropriate stages, should be given around housing time in accordance with the farm's veterinary herd health plan - this will highlight the most appropriate treatment for that specific farm. Housing avoids repeated treatment which may select for resistant strains.

- All purchased cattle should be treated with a flukicide, the choice of which depends upon time of the year and local veterinary advice, before joining the herd.

- During a low risk year, treatment to kill mature flukes is given to at-risk cattle from January.

- In years when epidemiological data indicate a high risk of fasciolosis, a treatment with a flukicide effective against immatures should be given at housing and if necessary more than 8 weeks after the first treatment. A third treatment in January/February with a different drug may be required to remove adults which have subsequently developed. from any early stages, which were not susceptible to the previous flukicide treatments. Faecal samples may be taken to help confirm if such treatments are necessary.

- Milk withdrawal periods in dairy cattle may determine the timing for treatments and drug used, with treatment given during the dry period in dairy herds - consult your veterinary surgeon for the best advice.

Economics

Fencing off snail habitats is rarely practicable and in most situations is cost prohibitive as these farms are often extensive beef cattle enterprises. Drainage is cost prohibitive and certain farms are subject to environmental controls.

Black disease (Infectious necrotic hepatitis)

In the UK black disease is typically associated with migration of immature liver flukes during late summer/early autumn and can affect unvaccinated cattle and sheep of all ages. Clinical signs are rarely observed and cattle are simply found dead.

There is no effective treatment. An appropriate fluke control plan, combined with an appropriate clostridial vaccination programme, should effectively control black disease.